There is a certain ache in my heart and head at having not been on the front lines in Charlottesville, Virginia. Every fiber of my being now wants to rush out to St. Louis, Missouri.

Twice now, Sahar Alsahlani, the leading Muslim activist who stood with Dr. Cornel West, Rev. Traci Blackmon, Rev. Dr. William Barber, and others, invited me to join her on her drives down south, my schedule not enabling me to participate. Sahar and I share the position of national co-chairs of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the oldest interfaith peace group in the U.S., and—as two of the few non-Christian leaders in the 100+ history of the organization—we remain acutely aware of our responsibilities as Muslim and Jewish spokespeople. What then, peering at the photos of the pastors and one Muslim woman standing up against 21st century Nazis and other assorted fascists and bullies, am I to make of no yarmulke-clad brethren on those front lines?

Twice now, Sahar Alsahlani, the leading Muslim activist who stood with Dr. Cornel West, Rev. Traci Blackmon, Rev. Dr. William Barber, and others, invited me to join her on her drives down south, my schedule not enabling me to participate. Sahar and I share the position of national co-chairs of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the oldest interfaith peace group in the U.S., and—as two of the few non-Christian leaders in the 100+ history of the organization—we remain acutely aware of our responsibilities as Muslim and Jewish spokespeople. What then, peering at the photos of the pastors and one Muslim woman standing up against 21st century Nazis and other assorted fascists and bullies, am I to make of no yarmulke-clad brethren on those front lines?

It is not, of course, that Jews should necessarily have a special responsibility for fighting 21st-century neo-Nazis, Klansman, racist police, and the “alt-right.” It is, however, this special time of year—a time of New Year joys and reflections, days of atonement for the year past and days of future prayer and planning—the “Feast of the Trumpet” to shout out to all the peoples of the world that humanity is born anew, and we are one.

Iconic British songwriter and artist Leon Rosselson writes about “that precious strand of Jewishness that challenges authority.” He was not, to be sure, assigning something special to theological devotion; if anything, he is more of the camp identified by another great musician, Dave Lippman, as “devout Jewish atheism”—with a greater appreciation of cultural heritage then contemporary political norms. Zionism, it must be understood, is (among other things) profoundly anti-Diasporic. Its very basis is the negation of a Judaism that does not accept the Holy Land as its center; it exists in direct contrast to the growing number of a new generation of people of Jewish descent, from every corner of the world, who are rejecting the colonial-imperialist, militaristic nationalism of the so-called Jewish state.

These youths trumpet out the cry “If not now?!” as they proclaim that theirs will be the generation “that ends our community’s support for the occupation.” Solidarity with the people of Palestine must be a prerogative for 5778, a special responsibility to fight back against the ever-intensifying incursions of the apartheid wall and policies which make anyone second-class citizens or worse on their own land. From the false borders parsing the West Bank and Gaza into smaller and smaller pieces, to the threatened new walls further dividing the people of Mexico from their northern sisteren and brethren, to the prisons and jails which make the U.S.A. today the world’s leader in rates of incarceration, it is time to tear down the walls.

These youths trumpet out the cry “If not now?!” as they proclaim that theirs will be the generation “that ends our community’s support for the occupation.” Solidarity with the people of Palestine must be a prerogative for 5778, a special responsibility to fight back against the ever-intensifying incursions of the apartheid wall and policies which make anyone second-class citizens or worse on their own land. From the false borders parsing the West Bank and Gaza into smaller and smaller pieces, to the threatened new walls further dividing the people of Mexico from their northern sisteren and brethren, to the prisons and jails which make the U.S.A. today the world’s leader in rates of incarceration, it is time to tear down the walls.

5778 is a year to trumpet the cause of political prisoners. With the historic release of Puerto Rican patriot Oscar Lopez Rivera, the “Mandela of the Americas,” after over 35 years behind bars for the thought crime of seditious conspiracy, we must re-double our efforts to break the prison industrial complex. Of special concern to all the peoples of the Abrahamic traditions should be the case of Imam Jamil Al-Amin, the Muslim cleric formally known as H. Rap Brown. A fiery chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Al-Amin is one of many former members of the Black Panthers still imprisoned after decades of trumped-up charges, disproportionate sentences, and/or torturous conditions. Sundiata Acoli, Mutulu Shakur, Russell Maroon Shoatz, Ruchell Magee, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Veronza Bowers, Roberta Seth Hayes, Jalil Muntaqim, and Herman Bell (brutally assaulted just this month by a gang of prison guards), are but a few of the former Panthers currently serving hundreds of years of collective time. Like the biblical Joshua and his trumpets sounding out around Jericho, we must bring those walls down!

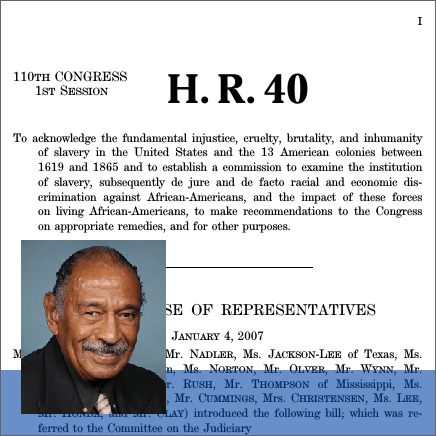

This is a year to trumpet the cause of reparations. After Charlottesville, three years after Ferguson, and all that has gone on in between, it is time to fully grasp what economist Boyce Watkins has noted: that “ending white supremacy means reparations and full economic justice.” There are many parts of U.S. reality in need of deep repair, and many meanings and means of implementing reparations. For veteran civil rights activist and Congressman John Conyers, however, who co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus and is the ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, it can only truly be about one thing. Reparations, according to Conyers’ House proposal to establish an investigatory commission on the subject, is deeply rooted in finally remedying the inhumanity of slavery and post-civil war racial injustice inflicted upon people of African descent “from 1619 to the present,” from the colonies to contemporary U.S. society. One could, of course, go back much further. The Torah speaks of “jubilee” in the Book of Leviticus, a concept of atonement and salvation linked directly to the ending of slavery in Egypt. Once reparations are granted to those who have been wronged, we may “proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants.”

This is a year to trumpet the cause of reparations. After Charlottesville, three years after Ferguson, and all that has gone on in between, it is time to fully grasp what economist Boyce Watkins has noted: that “ending white supremacy means reparations and full economic justice.” There are many parts of U.S. reality in need of deep repair, and many meanings and means of implementing reparations. For veteran civil rights activist and Congressman John Conyers, however, who co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus and is the ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, it can only truly be about one thing. Reparations, according to Conyers’ House proposal to establish an investigatory commission on the subject, is deeply rooted in finally remedying the inhumanity of slavery and post-civil war racial injustice inflicted upon people of African descent “from 1619 to the present,” from the colonies to contemporary U.S. society. One could, of course, go back much further. The Torah speaks of “jubilee” in the Book of Leviticus, a concept of atonement and salvation linked directly to the ending of slavery in Egypt. Once reparations are granted to those who have been wronged, we may “proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants.”

This is a year to trumpet the cause of revolutionary love and nonviolence. As the prophet Isaiah proclaimed, peace-makers and justice-seekers have a responsibility to rebuild the world on firm foundations of morality, decency, and equality—to become “repairers of the breach.” Rev. Dr. William Barber II, in proclaiming a new Poor People’s Campaign for a new era of coalition politics, has noted that “white nationalists staged a violent confrontation in Charlottesville because they have been emboldened by politicians who endorse white nationalist policies. We who believe in freedom and justice must make clear what a moral agenda for the common good looks like.” Condemning acts of racial violence is not enough; confrontational showdowns with wannabe fascists is insufficient. We must demonstrate through our deeds the meaning of solidarity: through our alternative institutions we create the meaning of fairness, and through our actions the meaning of life-long resistance, reconciliation, and righteousness. Only then will a radical shift in economic and political priorities be possible.

This is a year to trumpet the global movement of indigenous resistance to empire. My dear brother Ali Issa of the War Resisters League is the literal trumpet blower of the family; WRL’s work against the militarization of the police recognizes that “the arms industry has become increasingly intimate with law enforcement and emergency response agencies” and that the communities most affected by this imperial policing must also be the ones most empowered to fight back. As growing numbers of anti-war veterans call for an About Face against all wars, activists on the ground in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and in the “inner cities” of the empire fight back against all odds in creative, inspiring ways. In Ramallah, Palestine, a Quaker school continues to educate for liberation; its director, Joyce Ajlouny, was just named Secretary-General of the world-wide American Friends Service Committee. In Nagasaki, Japan, survivors of the atomic bomb which ended the last World War continue to lead the fight—with staunch support from the International Peace Bureau and others—for “peace waves” against any further global conflagrations or uses of the most devastating weapons humankind has produced.

This is a year to trumpet the global movement of indigenous resistance to empire. My dear brother Ali Issa of the War Resisters League is the literal trumpet blower of the family; WRL’s work against the militarization of the police recognizes that “the arms industry has become increasingly intimate with law enforcement and emergency response agencies” and that the communities most affected by this imperial policing must also be the ones most empowered to fight back. As growing numbers of anti-war veterans call for an About Face against all wars, activists on the ground in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and in the “inner cities” of the empire fight back against all odds in creative, inspiring ways. In Ramallah, Palestine, a Quaker school continues to educate for liberation; its director, Joyce Ajlouny, was just named Secretary-General of the world-wide American Friends Service Committee. In Nagasaki, Japan, survivors of the atomic bomb which ended the last World War continue to lead the fight—with staunch support from the International Peace Bureau and others—for “peace waves” against any further global conflagrations or uses of the most devastating weapons humankind has produced.

Closer to home in more ways than one, the Alliance for Jewish Renewal brought together a broad spectrum of faithful people to the multi-faith Community of Living Traditions(CLT) at Stony Point Center in Rockland County, New York—just down the street from the FOR headquarters in Nyack. Focusing on our responsibility to the environment and one another, the theme of this special gathering was “L’takken Olam: Healing all the worlds-No Exceptions!” A highlight for this participant was an outdoor ceremony at the close of the Sabbath, taking silent moments to connect directly, physically, and deeply with the nature surrounding us. Some of that service was prepared under the leadership of Rabbi Arthur Waskow of The Shalom Center, who challenges us to reflect upon how we would conduct prayer—and transform our language, ceremonies and actions—“as if the earth really mattered.”

Closer to home in more ways than one, the Alliance for Jewish Renewal brought together a broad spectrum of faithful people to the multi-faith Community of Living Traditions(CLT) at Stony Point Center in Rockland County, New York—just down the street from the FOR headquarters in Nyack. Focusing on our responsibility to the environment and one another, the theme of this special gathering was “L’takken Olam: Healing all the worlds-No Exceptions!” A highlight for this participant was an outdoor ceremony at the close of the Sabbath, taking silent moments to connect directly, physically, and deeply with the nature surrounding us. Some of that service was prepared under the leadership of Rabbi Arthur Waskow of The Shalom Center, who challenges us to reflect upon how we would conduct prayer—and transform our language, ceremonies and actions—“as if the earth really mattered.”

In Charlottesville, we learned that more mundane issues of basic safety were at the forefront. Congregation Beth Israel president Alan Zimmerman wrote painfully that Sabbath services during the “Unite the Right” weekend were surrounded by alt-right protesters shouting pro-Hitler slogans, confronted by Nazi websites calling for the synagogue to be burned to the ground, and concluded with a decision on the part of the temple to have congregants leave out of the back door, with a late afternoon event cancelled for fear of further harassment. Though there is a basic understanding that the alt-right agenda has most to do with an allegiance to white supremacy, and so much of the past two generations of Jews in America and the world have succeeded in “becoming white,” there is an additional dynamic taking place. The perverse revisionism which seeks a return to the “great America” of pre-civil rights, pre-civil war, free enslaved African labor days, relies in part on an extensive fetishism of the Third Reich, complete with old-fashioned anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, and pro-“industrial” capitalist policies. The contradictions have led to calls for the President’s closest Jewish advisors (including his son-in-law) to more publicly denounce him, and seen denunciations of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs president for being soft on Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon. But it is hard to feel like these re-actions (they barely classify as actions) adequately address the moment at hand.

Responding quickly enough to these anxious, dangerous, urgent moments is our biggest challenge today. As protests and rebellions spread out on the streets of St. Louis following the acquittal of the third racist killer cop in as many years, my Muslim brother David Ragland and I stayed up late into the night and wee hours of the morning lamenting how slow our organizations are at dealing with the crisis facing the people we work so hard to serve. Ragland is a native of Ferguson, Missouri, a co-founder of the Truth Telling Project which has always understood that we can have no reconciliation without reparations, no justice or peace without a shared understanding about the truth of what the U.S. is and has been. He is also the leader of a developing FOR program of reparations—a program we hope will trumpet out a new kind of solidarity, a new accountability against institutionalized white supremacy. David reminds me that tzedakah—more a moral obligation to heal society than a paternalistic charity—might this year be given to the bail funds set up for those arrested protesting the violence of everyday life in a society obsessed with race and class.

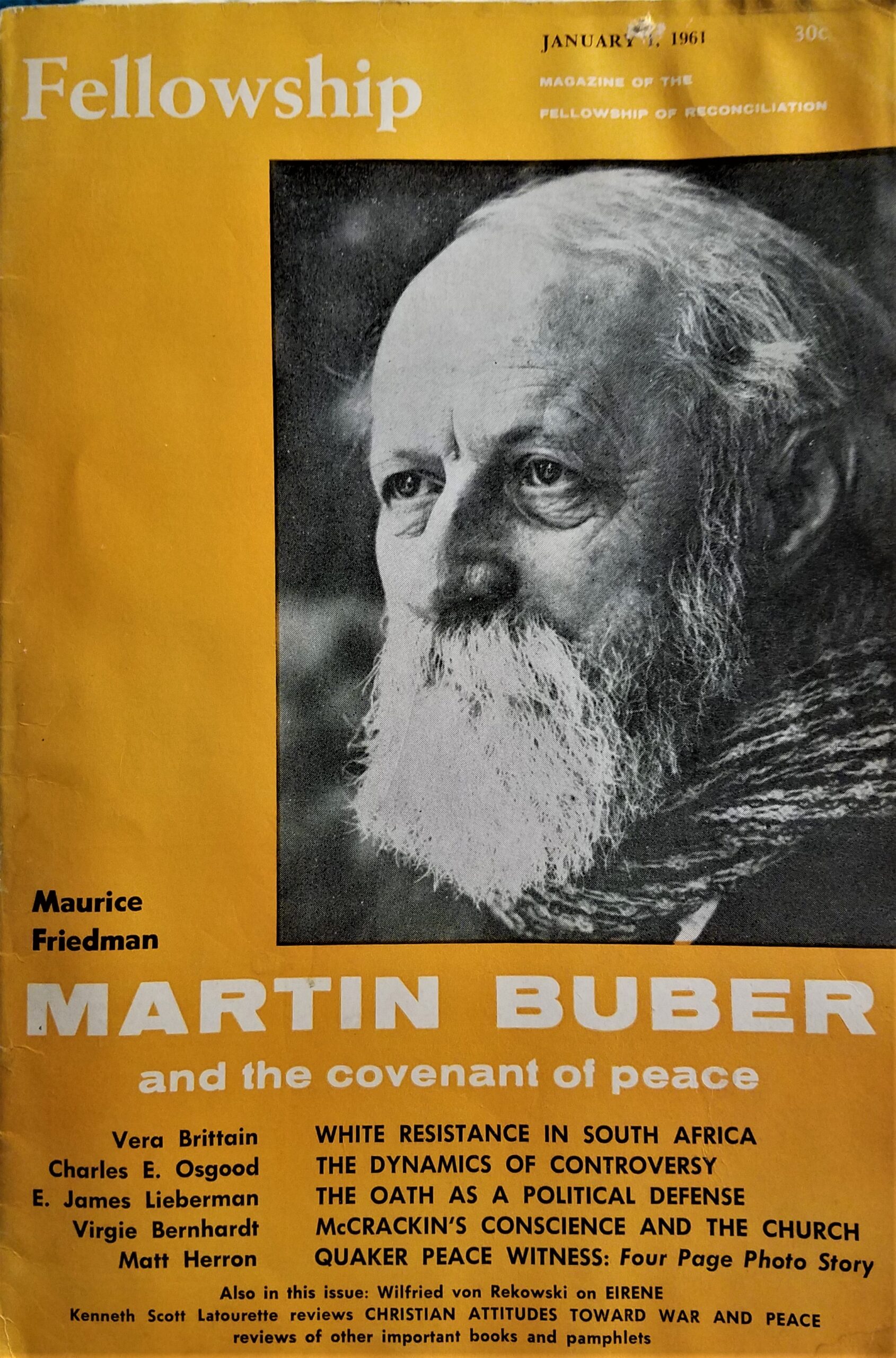

Perhaps it is time, as the trumpets sound and the shofars blow, as we prepare for new movements and a new year, to return to some basics. At the start of 1961, Fellowshipmagazine ran a lead story on Jewish scholar and mystic Martin Buber and his insistence on a biblical call that we reach out across ideological lines to uphold “a covenant of peace.” In Buber’s eyes, justice and peace is made not primarily through conciliatory words or humane projects or good intentions and faith. It is on the borderline between communities, the boundaries between nation-states, and the tough spots between people who may not look or act or believe exactly the way we do. Building in those spaces, organizing well beyond the choir, is what will make the peacemaker, in Buber’s words: “God’s fellow worker.” If we take these words to heart, we have little choice but to find ourselves, in 5778 and beyond, more quickly and decisively on the front lines of struggle.

Perhaps it is time, as the trumpets sound and the shofars blow, as we prepare for new movements and a new year, to return to some basics. At the start of 1961, Fellowshipmagazine ran a lead story on Jewish scholar and mystic Martin Buber and his insistence on a biblical call that we reach out across ideological lines to uphold “a covenant of peace.” In Buber’s eyes, justice and peace is made not primarily through conciliatory words or humane projects or good intentions and faith. It is on the borderline between communities, the boundaries between nation-states, and the tough spots between people who may not look or act or believe exactly the way we do. Building in those spaces, organizing well beyond the choir, is what will make the peacemaker, in Buber’s words: “God’s fellow worker.” If we take these words to heart, we have little choice but to find ourselves, in 5778 and beyond, more quickly and decisively on the front lines of struggle.

[Photos and images: (1) Faith leaders led by the Congregate Charlottesville coalition stand together on Saturday, August 12, 2017 in the midst of escalating tensions in downtown Charlottesville during the white nationalist “Unite the Right” rally, with Sahar Alsahlani (in black), Co-Chair of FOR’s National Council in the center of the line — photo by Edu Bayer, (c) The New York Times; (2) Community of Living Traditions member Eddie Erlich blowing the shofar (inset: Stony Point Center Annual Gala on Sept. 10, 2017, showing the ceremony where the 2017 Living Traditions Award was given to Jews for Racial and Economic Justice: from left to right, Zahara Zahav, Julia Carmel Salazar, and former Jewish Peace Fellowship & FOR staff member Joyce Bressler) — photo by Matt Meyer; (3) Congressman John Conyers, author of the Commission to Study Reparations Proposals to African-Americans Act, originally submitted during the 110th U.S. Congress and resubmitted during each Congressional legislative session since then — credit GovTrack.us; (4) Rabbis Phyllis Berman and Arthur Waskow of The Shalom Center, with Sahar Alsahlani and Matt Meyer — courtesy Matt Meyer; (3) Ali Issa blowing his trumpet — photo by Matt Meyer; (5) Front cover of the January 1, 1961 edition of Fellowship magazine.]