On May 16, 1942, every Japanese American in Seattle was either at an internment camp or on their way to one, except for one person. That day, Gordon Hirabayashi was at an FBI office in Seattle, in violation of an executive order from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, handing over a document to a special agent called “Why I Refuse to Register for Evacuation.”

On May 16, 1942, every Japanese American in Seattle was either at an internment camp or on their way to one, except for one person. That day, Gordon Hirabayashi was at an FBI office in Seattle, in violation of an executive order from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, handing over a document to a special agent called “Why I Refuse to Register for Evacuation.”

“This order for the mass evacuation of all persons of Japanese descent denies them the right to live,” it read. “It forces thousands of energetic, law abiding individuals to exist in a miserable physiological and a horrible physical atmosphere. …If I were to register and cooperate under those circumstances, I would be giving helpless consent to the denial of practically all of the things which give me incentive to live. …Therefore, I must refuse this order for evacuation.”

Over the course of the following year, Hirabayashi spent his time embroiled in court cases challenging the legality of the internment of Japanese Americans. His case, for which FOR raised money, made it to the Supreme Court.

In a year when the Republican Party’s candidate for president has advocated banning Muslims from entering the country, Hirabayashi’s case is a pressing reminder of how easily discriminatory policies can be justified on supposed “national security concerns.” It is also reminiscent of the work the Fellowship of Reconciliation eventually engaged in to protect Japanese-Americans during World War II, and how FOR continues that work today in the Give Refugees Rest campaign that challenges Islamophobic rhetoric.

As with the vast majority of those sent to internment camps, Hibayashi hardly fit the profile of someone who was a national security threat. He was, first of all, a pacifist: a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a Quaker, and a conscientious objector. He was a senior at the University of Washington at the time. He had never been to Japan in his life.

Through his religious convictions, he had come to stand against measures President Roosevelt had enacted following the bombing of Pearl Harbor that targeted Japanese Americans. He first broke a curfew that was imposed against Japanese Americans. When Roosevelt forced the internment of Japanese Americans, he wrote, he similarly felt that he had to oppose it.

“As removal from Seattle drew near, it occurred to me that if I couldn’t tolerate curfew, then how could I agree to be evacuated, which is much worse?” he wrote.

As a result, he wrote the document “Why I Refuse to Register for Evacuation” and spoke to a special agent at the FBI office, who wrote that Hibayasha “could not reconcile the will of God, a part of which was expressed in the Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution, with the order discriminating against Japanese aliens and American citizens of Japanese ancestry.”

Although FOR had for a while been reluctant to get involved in the issue of Japanese internment—Caleb Foote, who opened the Northern California office of FOR, wrote in March 1942 that “whether or not we should oppose this forced migration is still questionable in our minds”—members quickly became involved in Hirabayashi’s case. Shortly after Hirabayashi was arrested for his failure to comply with the evacuation, Washington state senator Mary Farquharson, a member of FOR, met with him and asked him if he was interested in turning his arrest into a test case of the constitutionality of the internment program. Other members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation—Bayard Rustin, John Nevin Sayre, and Caleb Foote—visited Hirabayashi in prison. Eventually, FOR decided to pay for Hirabayashi’s case.

This was not the only involvement FOR had in opposing the internment of Japanese Americans. Throughout late 1942 and early 1943, according to FBI files in the FOR archives, FOR held meetings at the Topaz center, an internment camp in Utah that held a total of over 11 thousand people. According to old issues of Fellowship, the organization also sent gifts to children at the camps and recruited families from the Midwest to house Japanese Americans “so that they may continue with their studies or engage in useful work instead of getting caught in mass evacuation.”

But the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s involvement in this case is perhaps the most significant work they did. It appears to have been a catalyst for the organization to begin its opposition against internment. It also is the one action FOR engaged in opposing Japanese internment that resulted in a Supreme Court decision.

But the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s involvement in this case is perhaps the most significant work they did. It appears to have been a catalyst for the organization to begin its opposition against internment. It also is the one action FOR engaged in opposing Japanese internment that resulted in a Supreme Court decision.

In 1943, the Supreme Court decided unanimously that the executive order requiring the evacuation of Japanese Americans was constitutional. It and subsequent rulings on the matter currently are considered some of the most infamous decisions of the Supreme Court.

Hirabayashi’s case did not die in 1943 with the failed Supreme Court case. In the 1980s, Peter Irons, a political science professor at the University of California, San Diego, uncovered documents that revealed that the government had withheld and destroyed documents that might have aided Hirabayashi’s case. Hirabayashi’s conviction was overturned in 1987, and in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which apologized and offered payments for the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Supreme Court decision, the internment of Japanese Americans, and the role of the Fellowship of Reconciliation show the fragility of the Constitution.

“The Constitution has guaranteed my protection regardless of race, sex, religion and so on, but it doesn’t guarantee that it’s going to be applied,” Hirabayashi said in an interview with a reporter for the Associated Press. “The citizens have to be vigilant to see that the Constitution is going to be applied in all cases.”

Hiribayashi v. The United States ended with a justification for the discrimination of Japanese Americans, a warning that the document that promises equal protection under the law can be twisted to disturbing effects.

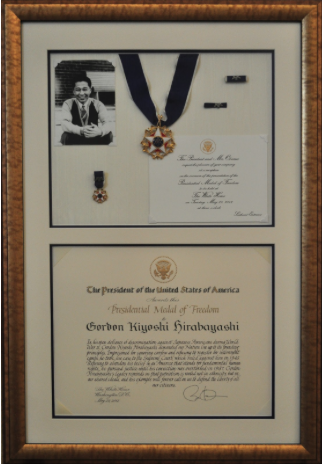

[Images: (1) Gordon Hirabayashi, Presidential Medal of Freedom, photographed during Courage in Action: the Life and Legacy of Gordon K. Hirabayashi. Courtesy of Creative Commons; (2) Panoramic view of Central Utah Relocation Center, Francis Stewart, 1943, National Archives and Records Administration]