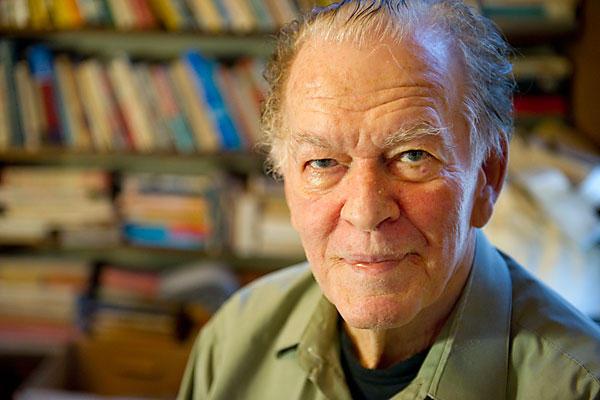

{Ed. Note: The recent death of Gene Sharp, the renowned strategist and thinker on active nonviolence, provokes us to newly consider his writings and teachings. René Wadlow revisits an essay he originally wrote during the period of the Arab Spring revolutions, and finds it timely for today’s framework of political resistance and revolutionary social change.]

The great problem of revolutionary action by the masses lies in this: how to find the methods of struggle which are worthy of men and which at the same time even the most heavily armed of reactionary powers will be unable to withstand. — Barthelemy de Ligt, The Conquest of Violence

The largely nonviolent people’s revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt followed by large protest demonstrations throughout the Arab world as well as Iran have drawn attention to the use of nonviolent strategies in the process of deep social change. When people want to end oppression and achieve greater freedoms and more justice, there are ways to do this realistically, effectively, self-reliantly, and by means that will last.

The largely nonviolent people’s revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt followed by large protest demonstrations throughout the Arab world as well as Iran have drawn attention to the use of nonviolent strategies in the process of deep social change. When people want to end oppression and achieve greater freedoms and more justice, there are ways to do this realistically, effectively, self-reliantly, and by means that will last.

Gene Sharp has been writing and talking about the strategies of nonviolent action for many years. I participated in two seminars that he led in Geneva in the late 1970s, and so I have read a good deal of his writings. Although he spent nine months in jail for objection to military service, followed by the limitations of parole for another year during the 1950-1953 Korean War, Sharp has been influenced by the thinking of military planning with the need to have a broad strategy which then leads to appropriate tactics. Thus some have called Sharp the “von Clausewitz” of nonviolent struggle.

The first step in strategy-building is a detailed analysis of the conflict situation, the strengths and weaknesses of the contending groups, and their sources of power. How do those strengths and weaknesses compare with each other? How might the respective strengths and weaknesses be changed? As Sharp wrote,

“To think strategically means to calculate how to act realistically in ways that change the situation so that achievement of the desired goal becomes more possible…How can people liberate themselves and develop the capacity to prevent the return of any system of oppression as they proceed to build a more free, democratic, and just society?”

Sharp has been read widely among anthropologists on what Robert MacIver called The Web of Government (1947). The web is made of institutions, attitudes, and cultural forms that structure a society and socialize most people to obey the norms. Sharp and his colleague Robert Helvey have called these sources of power “the pillars of support” for a regime. These sources of power “include the acceptance of the ruler’s right to rule (‘authority’), economic resources, manpower, military capacity, knowledge, skills, administration, police, prisons, courts, and the like. Each of these sources is in turn closely related to, or directly dependent upon, the degree of cooperation, submission, obedience, and assistance that the ruler is able to obtain from his subjects. These include both the general population and his paid ‘helpers’ and agents”. Thus the ruler’s power is not monolithic and permanent, but instead is always based upon an intricate and fragile structure of human and institutional relationship.

The pillars of support of a regime are always more fragile than they seem at first. As Karl Deutsch noted in his studies of political communities, “Totalitarian power is strong only if it does not have to be used too often. If totalitarian power must be used at all times against the entire population, it is unlikely to remain for long.”

Much of Sharp’s strategic approach is based on insights of Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi that the power of any government is dependent on the cooperation — the obedience — with the orders of the rulers. That is why the term noncooperation takes on its strategic meaning. Noncooperation is a large class of methods of nonviolent actions that involve deliberate withholding of social, economic, or political activity. Thus Sharp pays a good deal of attention to the techniques of noncooperation of labor movements — strikes, walkouts, boycotts, slowdown of production, etc.

Much of Sharp’s strategic approach is based on insights of Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi that the power of any government is dependent on the cooperation — the obedience — with the orders of the rulers. That is why the term noncooperation takes on its strategic meaning. Noncooperation is a large class of methods of nonviolent actions that involve deliberate withholding of social, economic, or political activity. Thus Sharp pays a good deal of attention to the techniques of noncooperation of labor movements — strikes, walkouts, boycotts, slowdown of production, etc.

Once one has made a detailed analysis of the sources of power, the second step is an overall strategic approach to coordinate and direct all appropriate and available resources (human, political, economic, cultural) to obtain its objectives in a conflict. While there is often broad agreement at the level of analysis of the sources of support of a regime, there can be real differences in the articulation of aims. There are broadly three goals for action: conversion, compromise, and disintegration.

Conversion is the most optimistic. It is the hope that the opponents will have a change of heart and accept the objectives of the nonviolent group. The monarch will give up his or her absolute power and become a constitutional figurehead.

Compromise is the usual aim of many reform movements. The monarch continues to have a good deal of authority, but the powers of the parliament are strengthened.

Disintegration. The sources of power are so severed by noncooperation that the opponent’s system or government simply dissolves and is replaced by new institutions. The monarch goes into exile and the nobles become businesspersons.

Often there will not be full agreement on the goal — a “let us see what will happen” is often the first basis for action. Nevertheless, strategies are often shaped by goals, and there needs to be a certain level of common vision for action to be undertaken.

The third step is the tactics, the techniques of action appropriate to the setting and the culture. As the German sociologist Karl Mannheim wrote, “The techniques of revolution lag far behind the techniques of Government. Barricades, the symbols of revolution, are relics of an age when they were built up against cavalry.”

To be effective, one needs to know the wide range of possible nonviolent actions and the history of their use in past conflicts — just as the military need to understand the range of military techniques available and how they have been used in the past. As Sharp wrote:

“No easy answer to the problem of dictatorship exists. There are no effortless, safe ways by which people living under dictatorship can liberate themselves…Our past understanding of the nature of the problem of modern dictatorships, totalitarian movements, genocide, and political usurpation has been inadequate. Similarly, our understanding of the possible means of struggle against them, and of preventing their development has been incomplete. With inadequate understanding as the foundation of our policies, it is no wonder that they have proven ineffective.”

The people’s revolutions of the Middle East will ultimately be recognized for having added new tools and new examples to the range of nonviolent action.

[Photos: (1) Bahrain pro-democracy protest, Feb. 2011, by Lewa’a Alnasr, Creative Commons license; (2) Gene Sharp, courtesy of Albert Einstein Institute.]