SHEILA D. COLLINS:

SHEILA D. COLLINS:

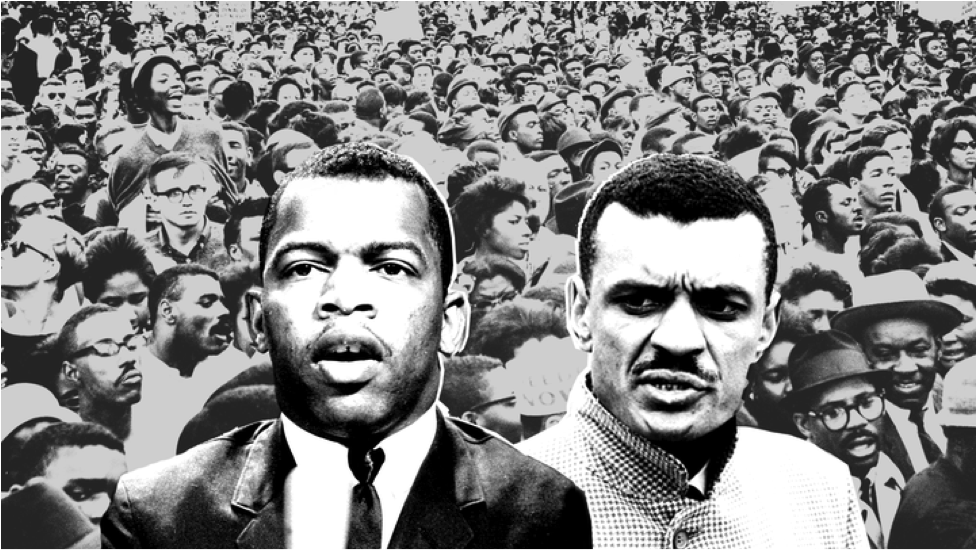

On July 18, 2020 we lost two valiant men—Rev. C.T. Vivian and representative John Lewis–icons of the civil rights movement, but so much more. Both men played leading roles in the civil rights movement of the late 1950s and 1960s, braving police beatings and frequent jailings and risking death many times over. Both were sharp critics of our country’s racist heritage yet somehow maintained their faith in this country and its capacity for change, while continuing to fight against racism and other forms of bigotry. Both men were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

I didn’t know John Lewis, the more recognized name of the two, but I did know C.T., as he was called, whose history was equally meritorious. C.T. was a member of Dr. King’s, inner circle of advisors and a coordinator of affiliates for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, leading nonviolent protests across the South. He was on the First Freedom ride, helped organize Tennessee’s contingent to the 1963 March on Washington, founded several important justice organizations including the Urban Training Center in Chicago and was deputy director for clergy in the 1984 Jesse Jackson for President campaign among other roles.

I first met C.T. in the late 1970s when I was directing a program for the Board of Homeland Ministries of the United Methodist Church that provided small grants and some technical assistance to a network of community-based organizations in poor black, Latino, Native American, Asian American and white communities around the country. During the course of my work, the late Jim Dunn, one of the black organizers with whom I worked had the idea of starting a national anti-racist training institute in community organization. Jim was a charismatic organizer and folk singer who could inspire in others a vision of the beloved community articulated by Dr. King and who had the commitment and the skill to bring people of different races together around that vision. When I first got to know Jim his community organization, which was based in Antioch, Ohio, was called “Help Us Make a Nation” or H.U.M.A.N. for short, the name implying everything that Jim stood for.

Together with other organizers who came to know each other through the program I directed Jim’s idea began to take on flesh. I was asked to be on the committee to plan what would eventually become the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond—an institution that, since Jim’s untimely death, has been faithfully carried on by his friend and organizer, Ron Chisom and Jim’s widow, Diana Dunn and a host of others. The Institute has since trained hundreds of thousands of people across the country and even abroad in undoing racism. C.T. Vivian was also a member of that planning committee, as was Anne Braden, a legendary white Southerner and one of the fiercest anti-racist whites I have ever met. C.T. was tall and wiry with seemingly boundless energy, a deep passion for justice, a smile that lit up his whole face, a rapid-fire staccato voice and a warm sense of humor. Despite all he had been through he seemed to bubble over with an infectious joi de vivre. C.T. said something once that I’ve never forgotten. “We in the civil rights movement,” he said, “always knew that we were marching for more than just civil rights. We were marching for constitutional democracy itself.” When I heard that for the first time a light opened up in my head. Of course, that was true. Why hadn’t I ever considered it? Perhaps it was a recognition of my own unconscious white liberal racism that I had perceived the struggle for civil rights as a struggle limited to black enfranchisement when it went far beyond that. The movement for Black Lives Matter, as many whites are now belatedly realizing, is a movement on behalf of humanity itself, a movement to finally make America what it should be but has never been.

My path continued to cross C.T.’s when we were both involved in an effort in the early 1980s to save the life of Eddie Carthan, a young man who had been the first African American since Reconstruction to be elected mayor of the black majority town of Tchula in the Mississippi Delta, in one of the poorest counties in the country. Shortly after his election, the white power structure offered Eddie a $10,000 bribe if he would be their “good little boy,” but when Eddie refused and appointed his own police chief, they went after him, framing him on three trumped up charges, the last being that of capital murder. Eddie was accused of murdering a local black drug dealer. One of the community organizations in the program I was running for the Methodist church, the United League of Holmes County, MS, had taken up Eddie’s case and its organizer, the late Arnett Lewis, a Vietnam vet, asked me to be on a national support committee. Arnett was a wonderful man, selfless and courageous, who had returned to organize his poor community after emerging from the war as the only survivor in his entire company.

The story of our struggle to save Eddie is also my family’s story as my husband, John, also got involved. The story is a long and sordid one of the way institutionalized racism works and the so-called “respectable” people and institutions that keep it going. During the discovery process we learned that the jury rolls had been rigged for over a century so that, even in a black majority county white names predominated. We also learned that the white power structure, which consisted of the leading lawyers, judges, business and plantation owners, were involved in a conspiracy to smuggle drugs from Latin America into Mississippi. The planes would land on the plantations and the drugs would then be circulated to the poor black community to keep them passive. When the legal team, the Christic Institute, which was run by a group of progressive Catholics in the mold of the Berrigan Brothers, tried to take the evidence they had uncovered to the F.B.I. they were told that the FBI couldn’t touch it, because it “went too high.” Indeed, it probably went as high as the governor’s office and perhaps higher in the Reagan administration.

Suffice it to say that through the efforts of the national support committee and the Christic Institute we were able to get Eddie exonerated after the longest trial in Mississippi’s history and the first all-black jury. While we had won a victory, the struggle was not without its victims. Before his trial, Eddie was forced to serve time in Mississippi’s notorious Parchment Prison. The Christic Institute subsequently lost all its funding and had to fold after it was accused of bringing “frivolous lawsuits.” Eddie Carthan’s application for a loan from the Farmer’s Home Administration (he was one of a small group of black landowners) was turned down by the man whom Reagan appointed to head the FHA—one of the very men behind the conspiracy to frame Eddie—a man, we discovered, who had been a member of the White Citizen’s Council in the 1960s, the “respectable” wing of the Klu Klux Klan. When the “respectable” Methodists of Holmes County learned that I was involved in Eddie’s support they threatened to withhold all their money from the national church unless the church got rid of me. I was put on a kind of trial by the United Methodist Church for my role in running the program through which I had gotten involved in this case, falsely accused of mismanaging money in an article that appeared in the New York Times, and subsequently lost my job.

I next worked with C.T. when we both worked for the Jesse Jackson for President campaign. Finding myself unemployed, at my husband’s suggestion I had gone to New Hampshire to volunteer for the campaign and soon found myself being told to get on a train to Washington, D.C to work as the campaign’s national “rainbow coordinator.” Jackson’s campaign was built around the idea of building a “rainbow coalition” of many races and ethnicities, as well as those whose primary identities came through their participation in various social movements, such as the peace movement, the environmental movement, the feminist movement, etc., or in particular occupations or locations, such as family farmers and low-income housing tenants. Key campaign leadership was provided by African Americans, but my role was to help mobilize the broader “rainbow” constituency. It was a wonderful learning experience, a real insight into the way the Democratic Party elites have shut out insurgent candidacies that articulate a more progressive direction for the country, and it became the basis for a Ph.D. dissertation and a book. I always wondered, however, why the campaign had hired me for this position. After all, I was an unknown, had had no previous campaign experience and did not know anyone within Jackson’s inner circle. I wonder now if it might have been C.T. who recommended me.

My life, and my family’s life, has been enriched for having known such people as C.T. Vivian, Jim and Diana Dunn, Ron Chisom, Anne Braden, Arnett Lewis, Eddie Carthan and so many others in the struggle for racial justice, for a new human community. I imagine those who have passed on conversing together over the remarkable multiracial movement that has blossomed after the killing of George Floyd. We owe it to them to continue the struggle.[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://forusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COLLINS-headshot.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Sheila D. Collins is professor emerita at William Paterson University and former director of its graduate program in Public Policy and International Affairs. She is the editor and author, with Gertrude Schaffner Goldberg, of When Government Helped: Learning from the Successes and Failures of the New Deal (Oxford University Press, 2013). She is the author of six books and numerous book chapters and articles on American politics and public policy.[/author_info] [/author]