Ever the undiscouraged, resolute, struggling soul of man;

Have former armies fail’d, then we send fresh armies – and fresh again

— Walt Whitman, “Life”

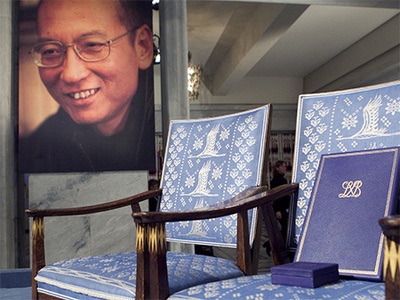

Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, died on July 13, 2017, at age 61 after having been jailed for 11 years for being a chief writer of an appeal for democratic and human rights reforms in China. Concern has been expressed for his wife Liu Xia, who has been under heavy survallance since the arrest of her husband. To honor his memory, the Association of World Citizens reprints an essay written at the time of the Nobel ceremony.

The chair for Liu Xiaobo was empty at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony on December 10, 2010, and there were a few other empty chairs of ambassadors from countries that had been constantly warned by Chinese emissaries that attendance at the ceremony would be considered an unfriendly act. However the spirits of the armies holding to Democratic Vistas were there.

The chair for Liu Xiaobo was empty at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony on December 10, 2010, and there were a few other empty chairs of ambassadors from countries that had been constantly warned by Chinese emissaries that attendance at the ceremony would be considered an unfriendly act. However the spirits of the armies holding to Democratic Vistas were there.

Walt Whitman, in Democratic Vistas, had denounced the depravity of the business classes and the widespread corruption, bribery, falsehood, and mal-administration in municipal, state, and national government. He was worried about the mal-distributation of wealth and the treatment of the working people by employers. Yet Whitman kept alive his ideal of social and political progress and the possibility of higher consciousness. Likewise, Liu Xiaobo and the other authors of Charter 08 are critical of the current trends of Chinese society but are firm in the hope that “all Chinese citizens who share this sense of crisis, responsibility and mission will put aside our differences to seek common ground to promote the great transformation of Chinese society.”

On Christmas Day 2009, a court convicted Liu of “inciting subversion of state power” and sentenced him to 11 years in prison and two additional years of deprivation of political rights. The verdict cited as evidence passages from six essays Liu published online between 2005 and 2007 and his role in drafting Charter 08, an online petition for democratic reform issued on December 9; 2008 which has since been co-signed by some 10,000 persons, mostly Chinese in China. This December 2010, Liu Xiaobo received the Nobel Prize for Peace, though his presence at the ceremony in Oslo was represented by an empty chair.

Liu Xiaobo’s case highlights one of the most crucial challenges facing the emerging Chinese civil society: the limits of freedom of expression. Liu Xiaobo not only offers his criticism of the regime but puts forth proposals to deal with crucial questions facing both the government and society, such as his essays on the future of Tibet.

Liu Xiaobo also reflects on the history of the relationship between the ruler and the ruled, and urges the Chinese people to awaken from a supplicant mentality shaped by a historical system continued to the present that has infantilized them. As he wrote:

“After the collapse of the Qing dynasty and especially after the CPC came to power, even though our countrymen no longer kowtow physically like the people of old, they kneel in their souls even more than the ancients…Can it be that Chinese people will never really grow up, that their character is forever deformed and week, and that they are only fit to, as if predestined by the stars, pray for and accept imperial mercy on themselves?”

His essays, since he returned to China from a visiting professorship at Columbia University in New York City in May 1989 to participate in the 1989 Democracy Movement, have infuriated the Chinese authorities with his hard, polemical style: “Driven by profit-making above all else, almost no officials are uncorrupted, not a single penny is clean, not a single word is honest… Degenerate imperial autocratic tradition, decadent money-worship, and the moribund communist dictatorship have combined to evolve into the worst sort of predatory capitalism.”

Liu Xiaobo stresses that China’s course toward a new, free society depends on bottom up reform based on self-consciousness among the people, and self-initiated, persistent, and continuously expanding nonviolent resistance based on moral values. He underlines the importance of New Age values that “Humans exist not only physically, but also spiritually, possessing a moral sense, the core of which is the dignity of being human. Our high regard for dignity is the natural source of our sense of justice.”

He sets out clearly the spirit and methods of nonviolent resistance in the current Chinese context.

“The greatness of nonviolent resistance is that even as man is faced with forceful tyranny and the resulting suffering, the victim responds to hate with love, to prejudice with tolerance, to arrogance with humility, to humiliation with dignity, and to violence with reason. The victim, with a love that is humble and dignified takes the initiative to invite the victimizer to return to the rules of reason, peace, and compassion, thereby transcending the vicious cycle of ‘replacing one tyranny with another.’ Regardless of how great the freedom-denying power of a regime and its institutions is, every individual should still fight to the best of his/her ability to live as a free person and make every effort to live an honest life with dignity…

“The nonviolent rights-defense movement does not aim to seize political power, but is committed to building a humane society where one can live with dignity… The nonviolent rights-defense movement need not pursue a grand goal of complete transformation. Instead it is committed to putting freedom into practice in everyday life through initiation of ideas, expression of opinions and rights-defense actions, and particularly through the continuous accumulation of each and every rights-defense case, to accrue moral and justice resources, organizational resources, and maneuvering experience in the civic sector. When the civic forces are not yet strong enough to change the macro-political environment at large, they can at least rely on personal conscience and small-group cooperation to change the small micro-political environment within their reach.”

Liu Xiaobo thus joins those champions of nonviolent action, such as Martin Luther King and the Dalai Lama, who have been recognized by the Nobel Peace Prize. The spirit of the New Age is rising in the East and is manifesting itself in nonviolent action to accelerate human dignity — a trend to watch closely and to encourage.

[Note: The text of the six essays cited in the trial for “inciting subversion of state power” and a translation into English is in the No. 1, 2010 issue of China Rights Forum published by Human Rights in China.]