On Christmas Day 2017, Pope Francis prayed for peace between Israelis and Palestinians, “that a negotiated solution can finally be reached, one that would allow the peaceful coexistence of two states within mutually agreed and internationally recognized borders.”

Essential to joining my prayer with Francis’ are the experiences my wife and I had living in the Middle East from 1982-85 with a Quaker assignment of listening to Arabs, particularly to Palestinians, and to Jews, particularly Israeli Jews. It was impossible not to be persuaded by the powerful truth of both their national narratives. While at times some told their people’s story in ways that seem to exclude the truth of the other’s story, listening carefully to both led us again and again to an inescapable conclusion. These two peoples, Palestinians and Jews, both have historically real and internationally legitimate bone-deep national aspirations in the same small land.

I recall experiences leading a dozen interfaith study trips to the region in which Jews encountered powerful Palestinian personal accounts of their families’ multi-generational links to the land. And I remember Nabil Shaath, a senior PLO advisor, confessing to one such delegation how it was only as he personally got to know Israeli Jews that he became convinced that their sense of connection to the land was as deep and genuine as his own.

This powerful sense of connection to place that both peoples feel has been evident in bitter controversy over President Trump’s recent announcement that the U.S. will now “recognize Jerusalem as the Capital of Israel.” While Israel’s current right-wing government welcomed the announcement, many Israelis who seek peace with the Palestinians, including senior retired military and security officials, opposed Trump’s move. The announcement deeply angered Palestinians and frustrated Saudi and other Arab leaders on whom the White House appears to be depending for help in reaching a peace agreement.

According to a University of Maryland Critical Issues Poll, two-thirds of Americans oppose the United States unilaterally making this move now, and even Republicans are closely divided. An American Jewish Committee poll revealed that only 16% of American Jews support making the move immediately. The Union of Reform Judaism, the largest Jewish American religious denomination, and pro-Israel/pro-peace J Street were both critical of the president’s announcement.

The president and White House team entirely ignored two popular Israeli national heroes who wisely recognized the dangers of such a unilateral step apart from a comprehensive resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the fall of 1967, shortly after Israel won the Six-Day War and occupied Jerusalem, when a young impetuous Israeli soldier raised the Israeli flag over the city, General Moshe Dayan immediately ordered the flag to be taken down, warning that Jerusalem was too sensitive to be treated in such a cavalier manner. Then in 1995, despite strong support from AIPAC for the Dole/Gingrich Bill to move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s concern that the move could derail Israeli-Palestinian negotiations encouraged Senator Dianne Feinstein to successfully introduce an amendment that allowed the president to postpone the move based on “national security considerations.”

Former U.S. Ambassador Daniel C. Kurtzer, an Orthodox Jew and friend since 1982, suggested on December 7 in The Daily News that the simplest step the president could take now to mitigate the negative effects of his announcement would be to say the “United States recognizes Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and will recognize the city as Palestine’s Capital when a two-state solution has been achieved.”

In a keynote address at a J Street national meeting in June 2014, Kurtzer confessed that he was “dumbfounded by with how little resolve the U.S. pursued its own peace initiatives.” (See chapters 6 to 10 my memoir, Crossing Boundaries in the Americas, Vietnam, and the Middle East, for an account of a half-dozen failed U.S. peace initiatives.)

In the waning years of the Obama Administration, Kurtzer urged the U.S. to announce a framework for Israeli-Palestinian peace, and seek endorsement for the framework by the U.N. Security Council. (See his “Parameters: Model Framework for Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations” [PDF download].) If President Obama and Secretary Kerry had acted on Kurtrzer’s advice, I believe the U.S. would have made a much greater contribution to prospects for peace than by the positive but substantially ineffectual gesture of abstaining on the UNSC vote condemning Israeli settlements. (Thinking of what might be possible if Presidents Obama or Trump followed Ambassador Kurtzer’s advice, I am reminded of how I felt in March 1980 listening to Ambassador Robert White at his home in El Salvador on the night of Archbishop Romero’s assassination.)

On the future prospect of Israeli-Palestinian peace, after it took four decades (circa 1948-1988) for the “two-state” solution to gain general acceptance, the question of “two-states” or “one-state” is being given heightened attention today after President Trump said the U.S. would accept either depending on the parties’ agreement. The problem with the one-state idea – and why two states remains the only realistic solution – is that it’s not possible to imagine either side’s version of one-state being accepted by the other side.

On the future prospect of Israeli-Palestinian peace, after it took four decades (circa 1948-1988) for the “two-state” solution to gain general acceptance, the question of “two-states” or “one-state” is being given heightened attention today after President Trump said the U.S. would accept either depending on the parties’ agreement. The problem with the one-state idea – and why two states remains the only realistic solution – is that it’s not possible to imagine either side’s version of one-state being accepted by the other side.

Given demographic realities and trends, the Palestinian version of one-state – between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea with equal rights for all, which may sound good to some idealistic supporters of liberal democracy – would mean the end of Israel as a state with a Jewish majority. That’s something the vast majority of Jews in Israel and worldwide would not accept. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, establishing a Jewish majority state was fundamental to the creation of modern Israel.

Decades of steadfast popular nonviolent and violent resistance to Israeli occupation has shown that the Israeli version of one-state – with Israel continuing military control over large areas of the Occupied Territories while refusing voting rights to Palestinians in these territories – would never be accepted by the Palestinians. Pursuing either of these “one-state solutions” almost inevitably would mean years, maybe decades more violence, and likely new wars with unpredictable regional entanglements and possible catastrophic consequences.

While it may still be the only realistic solution, many question the viability of a two-state solution, primarily because of continuing Israeli settlement expansion in the Occupied Territories, including Jerusalem, but also because of ideological hostility and violent threats against Israel from Hamas and Hezbollah, with support from Iran. Weak, divided Palestinian political leadership, and Israel’s most right-wing government ever, currently compound doubts about the possibility of any negotiated solution.

Encouragingly, there are some positive signs.

After days of demonstrations protesting Trump’s Jerusalem announcement that cost the lives of 12 young Palestinians, news broke that 63 young Israelis publicly pledged not to enlist in the army to protest their government’s continued occupation and oppression of Palestinians.

On the popular level, there are strong and growing links through ONE VOICE and other networks between young Palestinian and Israeli peacemakers.

On the diplomatic level, negotiations during the Obama years generated the idea of one-for-one land swaps, now endorsed by the Arab League, that would allow Israel to keep some settlement blocks near the 1967 “border” (the “Greenline”), in exchange for Palestine getting equal parcels of land from Israel next to Gaza or the northern West Bank.

On the diplomatic level, negotiations during the Obama years generated the idea of one-for-one land swaps, now endorsed by the Arab League, that would allow Israel to keep some settlement blocks near the 1967 “border” (the “Greenline”), in exchange for Palestine getting equal parcels of land from Israel next to Gaza or the northern West Bank.

Politically, negotiations between Fatah and Hamas appear to be close to a reconciliation agreement that would strengthen the Palestinian Authority and commit Hamas to stopping violent attacks against Israel. While the Likud party continues to oppose two-states and recently called for annexation of some areas of the West Bank, two former hawkish leaders, Ariel Sharon and Ehud Olmert, left the Likud. Sharon pulled Israeli forces out of Gaza, and both publicly warned of the dangers to Israel of holding on to the Occupied Territories. At the Annapolis conference in 2007, then-Prime Minister Olmert declared to supporters, “If the day comes when the two-state solution collapses, and we face a South African-style struggle for equal voting rights, then, as soon as that happens, the State of Israel is finished.” On November 4, 2017, some 85,000 Israelis demonstrated in Tel Aviv under the banner, “We Are One People” to honor the memory of Prime Minister Rabin as peacemaker.

What the United States does in the coming months will affect if these positive signs are developed into renewed negotiations for a realistic two-state peace agreement or the situation slides toward more violence and war. The most important steps the U.S. could take would be to present a Framework for a two-state agreement, preferably coordinated with other members of the Quartet, namely the European Union, Russia, and the U.N. Secretary General, and present the Framework to the U.N. Security Council for endorsement.

The White House team, led by Jared Kushner and Jason Greenblatt, appears to be depending on help from Saudi and other Arab state leaders to help achieve a final peace agreement. This approach, if based on UNSC Resolution 242 and building on the Arab Peace Initiative, could help lead to a positive breakthrough. What’s worrisome are signs that the Trump Administration may be dangerously attempting to get a “deal” with Saudi Arabia that ignores or rejects essential Palestinian and international requirements for peace.

Even more alarming, on January 2, President Trump threatened to cut off aid to the Palestinians if they don’t return to negotiations with Israel; and, apparently contradicting his earlier statement about not deciding the final borders in Jerusalem, he said, “We’ve taken Jerusalem off the table.” If this latter statement represents current U.S. policy, it could kill chances for a negotiated peace.

Rather than simply wringing our hands and protesting, we need to continue to work together to advocate for what we believe the U.S. could and should do to help achieve a fair, realistic two-state peace agreement. (For a principled and practical analysis, see Daniel Kurtzer’s “Waiting for Uncle Sam” including “Ten Principles for Renewed U.S. Leadership,” in The Cairo Review of Global Affairs.)

In July 2017, leaders of 20 Jewish, Christian, and Muslim national organizations wrote to President Trump, saying that based on years of official and informal negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians, “the basic parameters for a two-state solution are widely known” and “combined with a broader regional framework such as the Arab Peace initiative, the incentives for all sides to make the historic decision for a two-state peace agreement are monumental.” The religious leaders believe “achieving a just peace would have substantial positive effects for both peoples, the region, the United States’ own interests, and our world.” They pledged “active support to achieve this goal” – let us all join together in making that commitment.

This prayer by Rabbi J. Rolando (Roly) Matalon of Congregation B’nai Jeshurun in New York – one of several multi-faith prayers I have collected through the years for the U.S. Interreligious Committee for Peace in the Middle East – is also my prayer:

O God Source of Life, Creator of Peace . . .

Help Your children, anguished and confused,

To understand the futility of hatred and violence

And grant them the ability to stretch across

Political, religious and national boundaries

So they may confront horror and fear

By continuing together

In the search for justice, peace, and truth. . . .

With every fiber of our being

We beg You, O God,

To help us not to fail nor falter.

All photos courtesy of Ron Young:

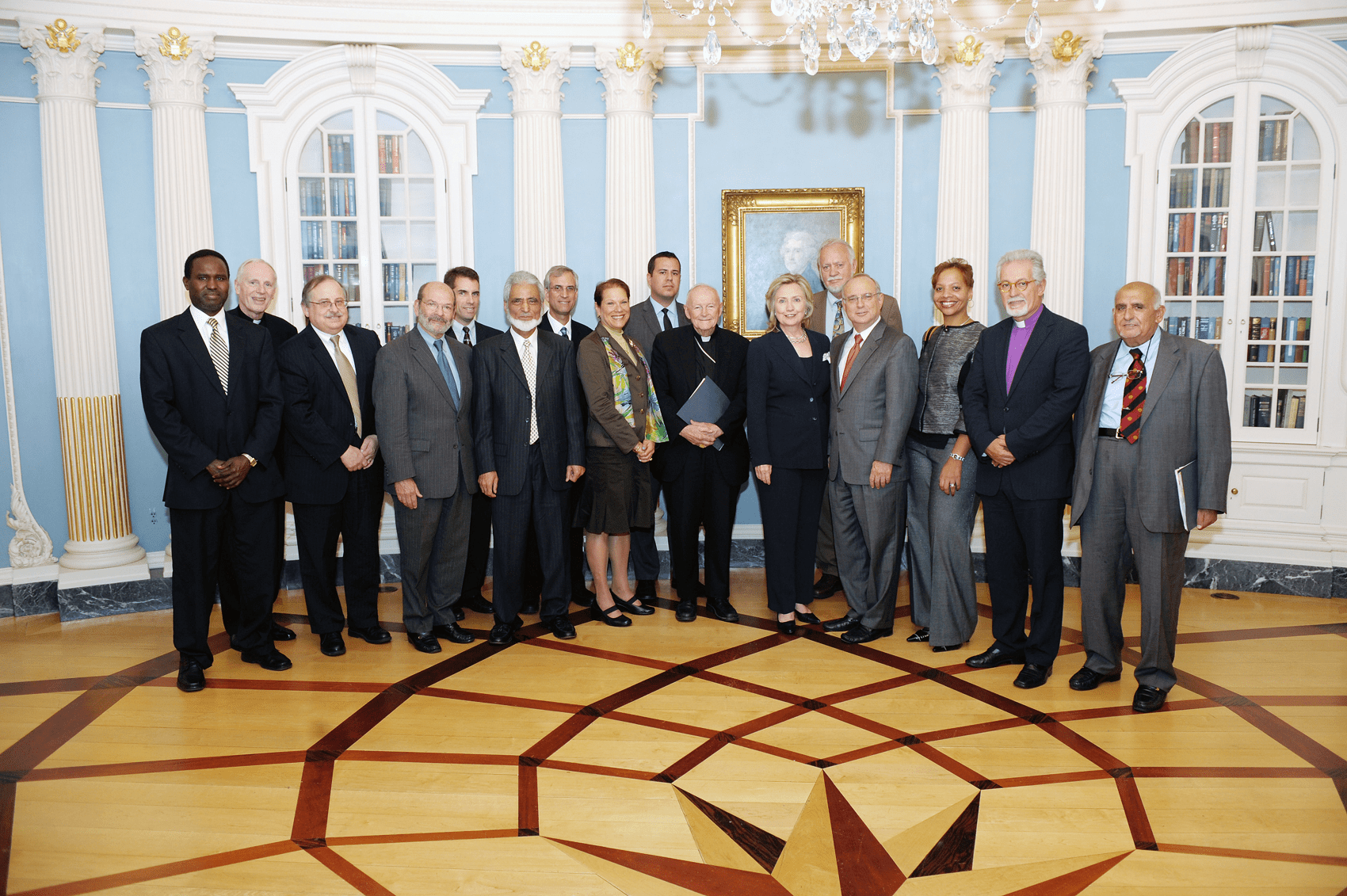

- Jewish, Christian, and Muslim leaders meet with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton after a 2009 trip to Israel/Palestine, organized by Ron Young.

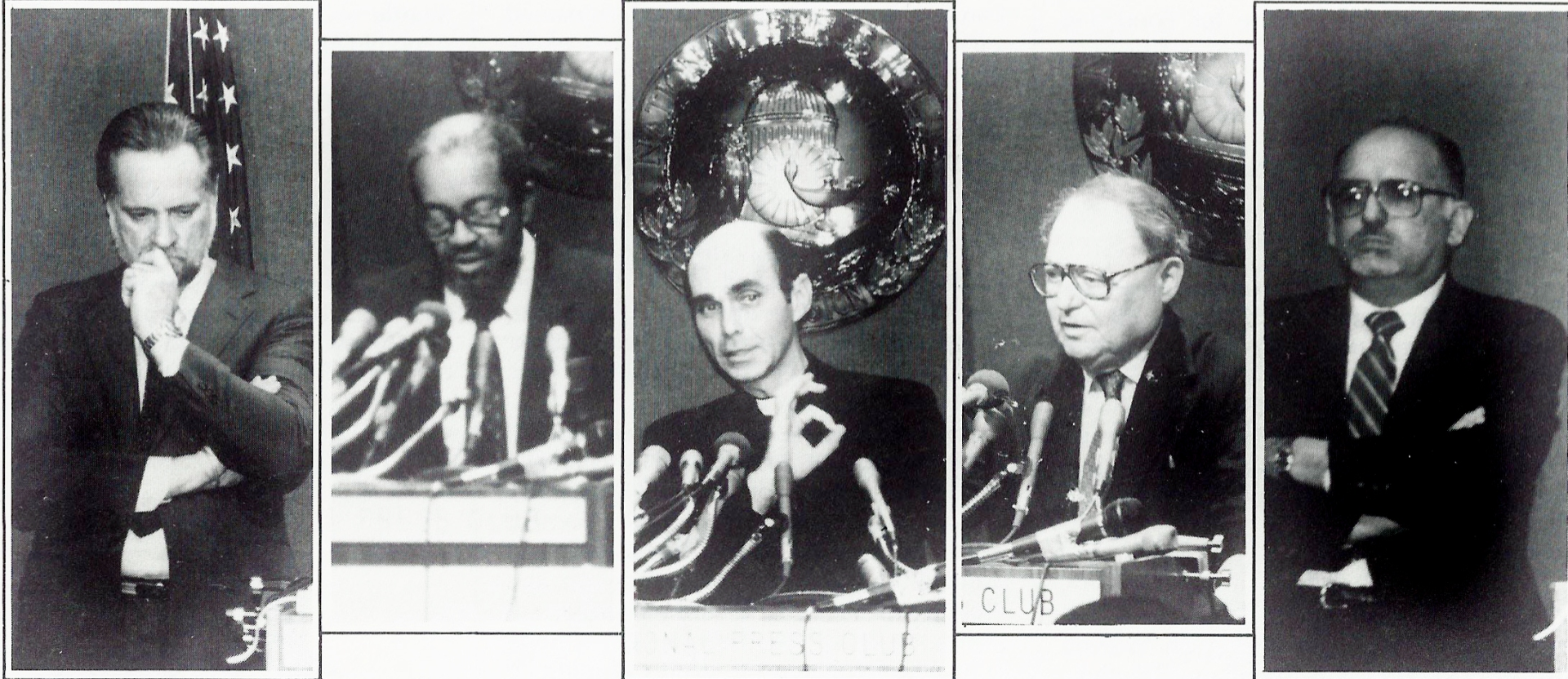

- Ron Young with founders of the U.S. Interreligious Committee for Peace in the Middle East (USICPME): W.D. Muhammed, Fr. J. Bryan Hehir, Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg, and Dawud Assad. (Rev. Joan Brown Campbell, a fifth founder, is missing from the photo.)

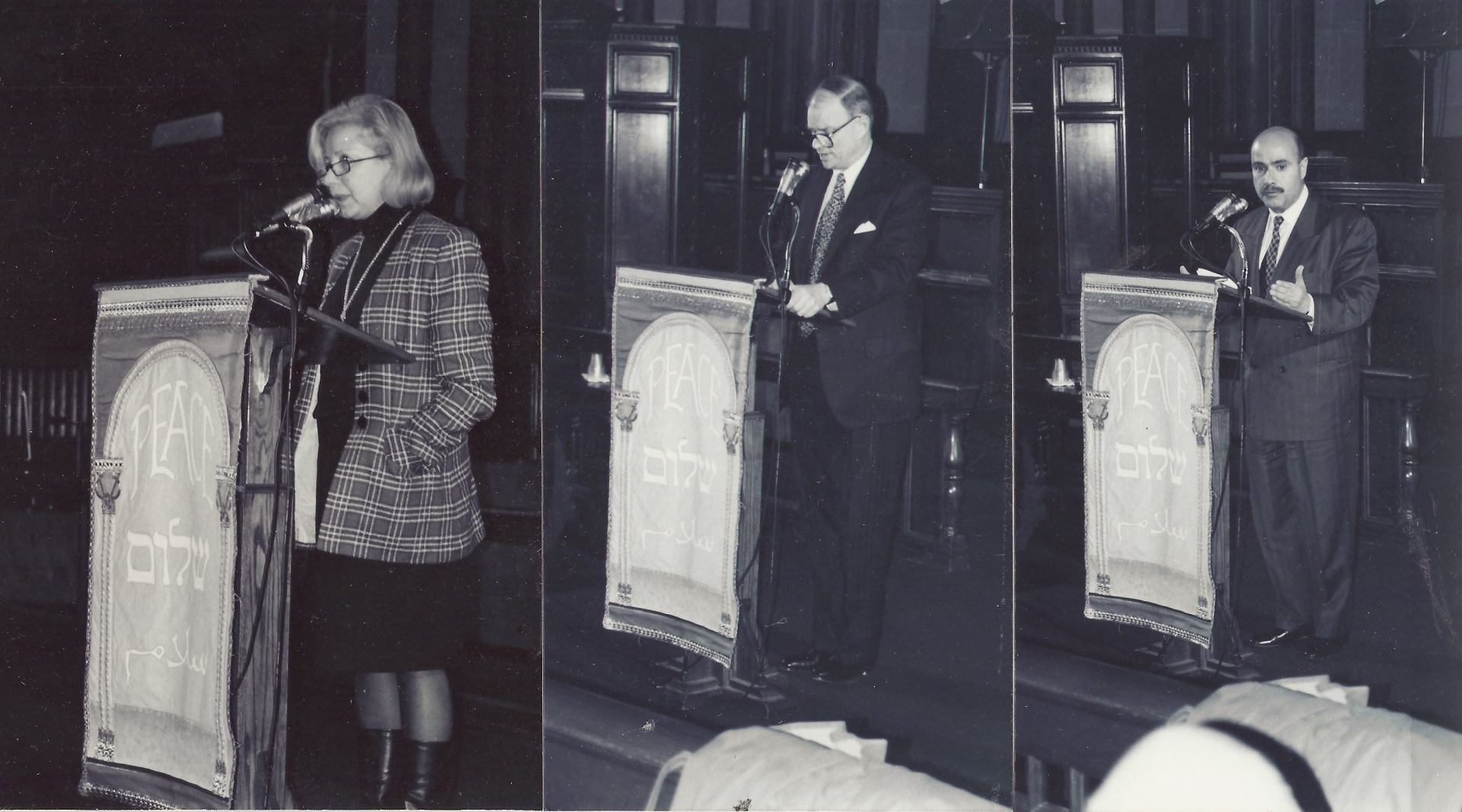

- Speakers at the USICPME Interfaith Evening for Peace at B’nai Jeshurun in New York: Israeli Consulate Colette Avital, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Robert Pelletreau, and PLO Representative Hassan Abdel Rahman.