Yesterday’s edition of “Take Two” — a daily radio program on Southern California Public Radio, broadcast via KPCC-89.3 FM (Pasadena CA) — featured a segment titled “How should California reconcile its (very) racist history?” The six-minute story centers on an interview with Benjamin Madley, a UCLA professor whose work focuses on the genocide of Indigenous peoples in the Americas, especially in California.

Framed in the context of the current national movement to remove statues and monuments dedicated to individuals who were slaveowners and otherwise involved on our nation’s racist foundations, the story reports, “Benjamin Madley said the names of the men responsible for the systemic oppression and killings of California’s native people continue to be ‘hidden in plain sight.'”

Earlier this year, FOR’s Fellowship magazine featured a lengthy book review by Mark C. Johnson, which put in conversation Prof. Madley’s new book An American Genocidewith two other important titles on Native peoples in the Americas. We now publish the review online here.

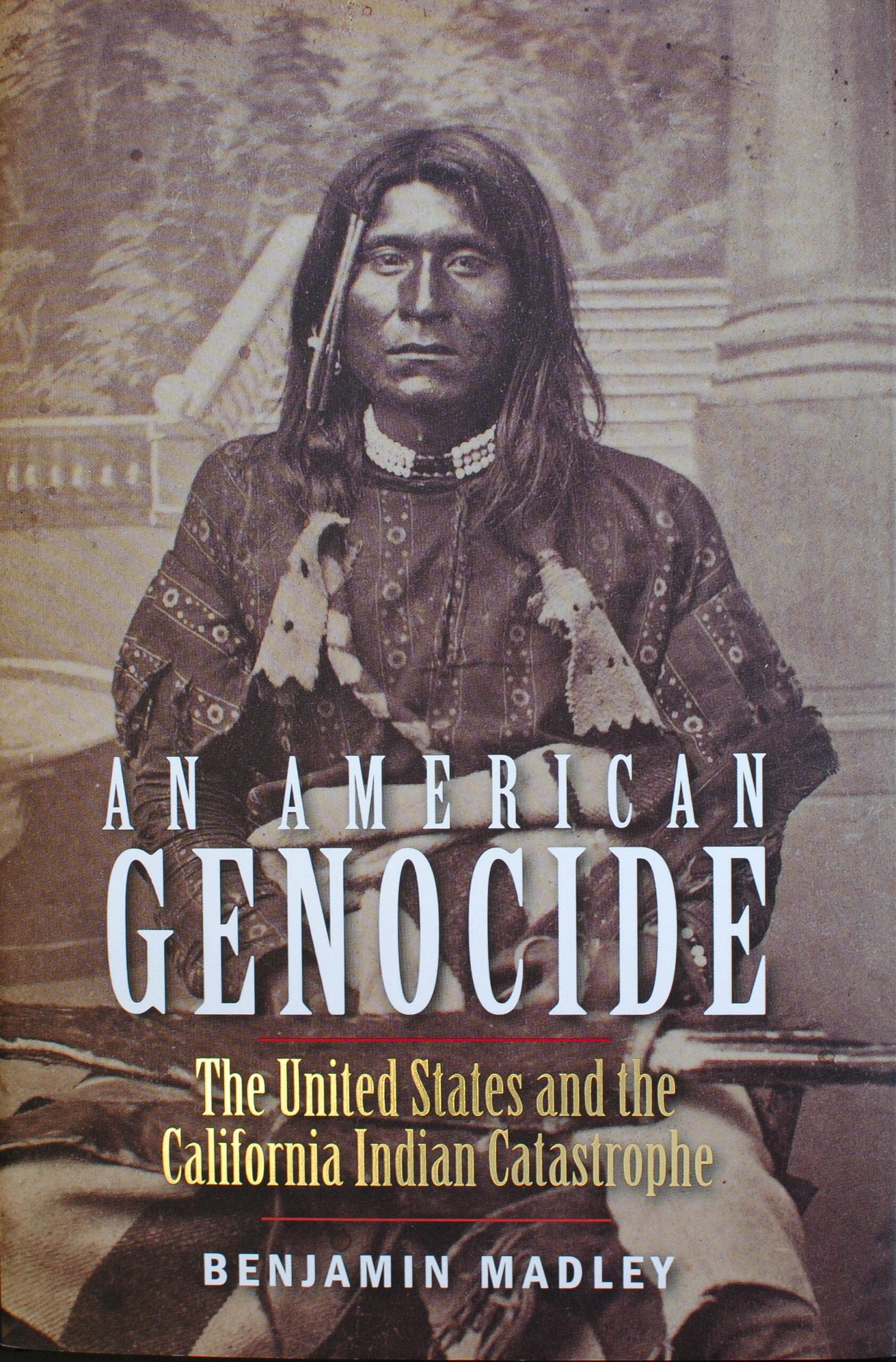

- An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 by Benjamin Madley (Yale University Press, 2016, 692 pages, $38.00)

- The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016, 431 pages, $30.00)

- Also discussed: Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Doctrine of Christian Discovery by Steven T. Newcomb (Fulcrum Publishing, 2008, 186 pages, $19.95)

Reviewed by Mark C. Johnson

The dust jacket of Benjamin Madley’s An American Genocide is graced by an 1864 sepia-toned portrait of the Modoc warrior Kintpuash, also known as Captain Jack, taken by T.N. Wood in front of a studio backdrop tapestry of a fountain, stone column, and stairway leading into a forest scene. With braided hair, beaded necklace, a quiver, and lap-blanket, his gaze is direct and yet suggests a somber reserve. He is quoted in a May 1873 correspondent’s letter in The New York Times explaining, “When I was a little boy, [California militia Captain] Ben Wright murdered my father and forty-three others who went into his camp to make peace” at the 1852 Lost River Massacre. Madley observes, drawing his 350-page analysis, full of such personalized stories, to a conclusion, “As a result of such experiences, the Modocs in the Stronghold likely expected the revival of the killing machine.”

The dust jacket of Benjamin Madley’s An American Genocide is graced by an 1864 sepia-toned portrait of the Modoc warrior Kintpuash, also known as Captain Jack, taken by T.N. Wood in front of a studio backdrop tapestry of a fountain, stone column, and stairway leading into a forest scene. With braided hair, beaded necklace, a quiver, and lap-blanket, his gaze is direct and yet suggests a somber reserve. He is quoted in a May 1873 correspondent’s letter in The New York Times explaining, “When I was a little boy, [California militia Captain] Ben Wright murdered my father and forty-three others who went into his camp to make peace” at the 1852 Lost River Massacre. Madley observes, drawing his 350-page analysis, full of such personalized stories, to a conclusion, “As a result of such experiences, the Modocs in the Stronghold likely expected the revival of the killing machine.”

A few pages on Madley continues, “…[A]t 10:20 A.M. on October 3, 1873, soldiers hanged Kintpuash, John Schonchin, Boston Charley, and Black Jim before cutting off and shipping their heads to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, DC. Thus ended the final act of the last major military campaign against California Indians, which had killed up to thirty-nine more Modocs,” in a blunt, understated, nearly overwhelming account of The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873, as the monograph is subtitled.

Making a case for using the most conservative of estimates of total populations and their decimation, Madley describes year by year, killing by killing, massacre by massacre – by private individuals, California militia, and U.S. federal troops – the reduction of 150,000 Californian Indians in 1846 (when U.S. warships anchored in Monterey Bay and took the State from Mexican control) to as few as 16,277 in the 1880 census. It is a gruesome detailing of the purposeful, explicit intention to wipe out, exterminate, annihilate, mass murder, starve to death, burn out, extirpate, kill every single Indian in every tribe. Madley finds his evidence in news reports, letters, legislative testimony, and forensic evidence at the local, state, and national level. It is exhaustive. (The text is accompanied by 200 pages of tables, notes, and bibliography of sources.)

The monograph also has a wonderful apparatus of photographs, drawings, and lithographs from the time as well as detailed maps. It is chronologically ordered, allowing the increasingly systematic nature of the process to unfold from the arbitrary vigilantism of the early gold rush era, to the “pedagogic violence” of state-supported militia, to the Civil War era of policy-driven extermination. The litany of cruelties is encyclopedic, the consequences genocidal in intent and in effect.

The larger framing-construct, and the academic discipline in which the monograph is presented, is the apt if anachronistic United Nations Genocide Convention (1948) built on the political theories of Raphael Lemkin (see Appendix 8). At the end, Madley says: “Thus, how we explain the Native American population catastrophe informs how we understand the making of the United States and its colonial origins. Beyond interpretations of US history, the stakes include important issues such as public acknowledgement, apology, reparations, natural resources, land, American Indian sovereignty, and national character. Despite these high stakes, the question remains unresolved, in part because of the deadlocked American genocide debate.”

Madley argues his is a modest contribution to the methodology of resolving the debate and that it should be replicated. But one cannot stand in the midst of the teepees of 10,000 Native Americans and their allies gathered prayerfully around the seven sacred council fires shared by hundreds of gathered Nations – looking at the militarized, mechanized, armored forces of the State of North Dakota on the banks of the Missouri River in the middle of Lakota Sioux Nations – without understanding how high the stakes are and what an important contribution Benjamin Madley has made to “…help all Americans, both Indian and non-Indian, to make more accurate sense of our past and our selves.”

Andrés Reséndez’s The Other Slavery takes us back to the economics of the Americas from the time of Columbus’s arrival up to the California gold rush. In so doing, he makes a case for the claim of the regionally specific nature of many practices, such as Indian Killing in California, as well as the more deeply embedded variety of causes that explain the collapse of Indian populations throughout the Americas over many centuries.

Andrés Reséndez’s The Other Slavery takes us back to the economics of the Americas from the time of Columbus’s arrival up to the California gold rush. In so doing, he makes a case for the claim of the regionally specific nature of many practices, such as Indian Killing in California, as well as the more deeply embedded variety of causes that explain the collapse of Indian populations throughout the Americas over many centuries.

According to Reséndez’s research, there was a preexisting practice of slavery among Indigenous peoples predating the arrival of Europeans, which became much more widely employed with more detrimental consequences throughout the long history of expanding occupation and resource extraction. We are reminded, for example, that the gold rush, a driver of Indian Killing in the 1840s and ‘50s, was but a brief blip compared to the centuries-long extraction of silver by the Spanish. Securing workers in statuses that range from indentured servants to peons to slaves put them in laboring roles of mining, which were brutal and life-taking in the extreme. The condition of slavery, argues Reséndez, contributes to more deaths overall than warfare, and is the principal causal contributor to deaths attributed to disease.

“If we were to add up all the Indian slaves taken in the New World from the time of Columbus to the end of the nineteenth century, the figure would run somewhere between 2.5 and 5 million slaves,” observes Reséndez. Nor were such slaves by any means confined to the control and employ of Europeans, or confined to the Americas. Efforts to ship Indians as slaves back to Europe were rather quickly contained by royal decrees banning the practice. But such decrees had virtually no impact on the practice in the Americas because it use was nearly universal across peoples, and because the distance made the practice uncontrollable.

The Navajo, Comanche, Apaches, and other Plains Indians were particularly adept in keeping and trading slaves, especially Mexicans, of which they were often descendants. New Mexico Chief Justice Kirby Benedict noted in 1865 that “nearly all propertied New Mexicans, whether Hispanic or Anglos held Indian slaves, primarily women and children of the Navajo nation….”

While neither Madley nor Reséndez make explicit reference to the Doctrine of Christian Discovery, expounded in the Inter Caetera papal bull of 1493, neither should be read independently of Steven T. Newcomb’s Pagans in the Promised Land.

When the dust jackets come off and their books are shelved, not starting with a grounding in the Doctrine of Discovery will make the experience like reading the Wizard of Oz without ever looking behind the screen. The stories are excellent and well told, but the deeper secrets are not revealed. For that you need to read Newcomb first.