by Paul R. Dekar for the 2020 Gandhi Peace Festival

This article was written for the Gandhi Peace Festival, hosted by the city of Hamilton, Ontario on October 2, 2020–the Mahatma’s birth date. -ED

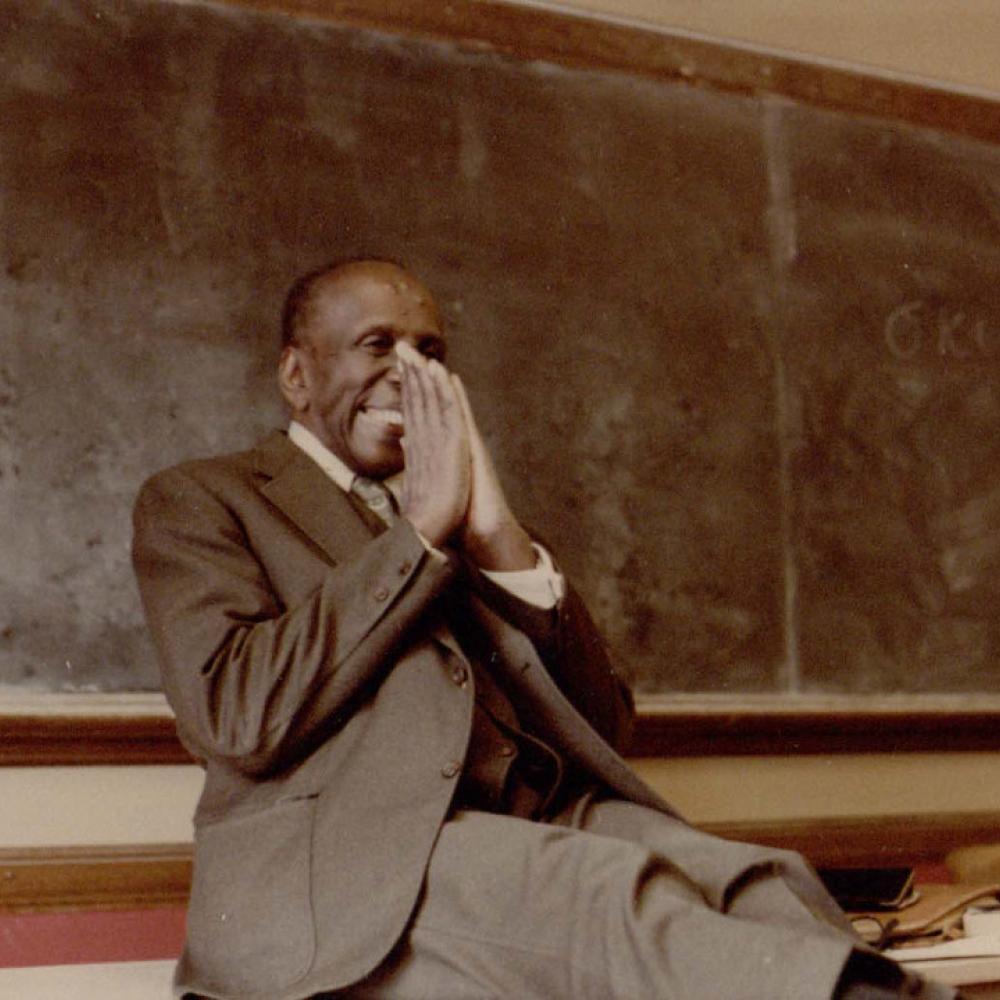

From the Howard Thurman and Sue Bailey Thurman Collections, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

By the 1920s, Gandhi had begun to influence civil rights activism in the U. S. John Haynes Holmes (1879-1964), a prominent Unitarian minister, reformer, and pacifist in World War I, was an early exponent of Gandhi’s ideas. He co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Holmes spoke of Gandhi in sermons entitled “The Christ of Today” and “Who is the Greatest Man in the World Today?” Gandhi’s Autobiography, The Story of My Experiment with Truth was first published in the U. S. in Unity, the magazine that Holmes edited.

Gandhi influenced members of several bodies, including the Religious Society of Friends, a historic peace church along with the Brethren and Mennonites. On a visit to India in 1926, Quaker leader Rufus Jones (1863-1948) interviewed Gandhi, who said to Jones, “Faith in the conquering power of love and truth has gone all the way through my inmost being and nothing in the universe can ever take it from me.” (The Testimony of the Soul, p. 163). In his autobiography, Jones highlighted Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha, a Sanskrit word loosely translated as nonviolence or soul force.

An organization whose members adopted the idea of satyagraha was the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR), an interfaith body begun during World War I in response to the horrors of war in Europe. After the war, IFOR members studied Gandhi’s writings. Many traveled to India where they adopted Gandhian nonviolence to delegitimize power and uproot such violence as segregation in administrative, economic, educational, and social spheres. IFOR now has 71 branches, groups, and affiliates in 48 countries on all continents.

Gandhi influenced the leadership of the civil rights movement including Ralph Abernathy, James Baldwin. Marian Wright Edelman, James Farmer, Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, A. Philip Randolph, James Herman Robinson, Bayard Rustin, Howard Thurman, and Congressman John Lewis. The latter’s death in July, 2020 highlighted the role of a remarkable generation of leaders who challenged racism. In this short essay, I can only cite a couple notable examples of Gandhian influence on the civil rights movement.

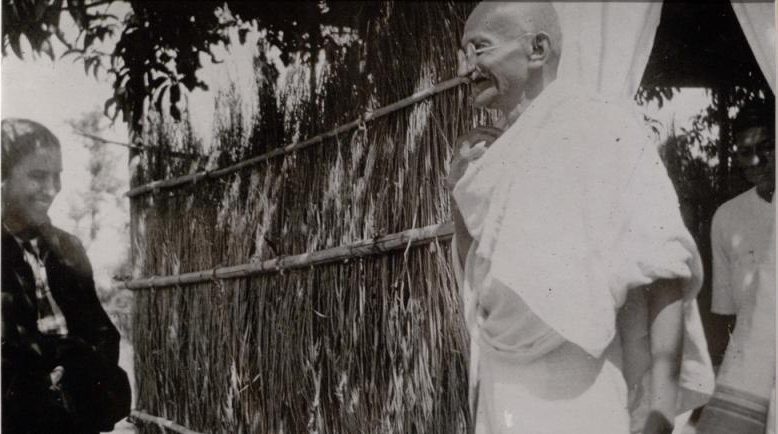

From the Howard Thurman and Sue Bailey Thurman Collections, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

In 1935, Baptist pastor, theologian, and educator Howard Thurman (1899-1981) was part of a delegation to India along with his wife Sue and two other African-Americans. Thurman met Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi. During an interview, Gandhi urged Thurman to return to the U. S. prepared to adopt what he learned in India. He told Thurman, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

At the end of their tour, the delegation stood at Khyber Pass, between what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan. As he looked out, Thurman reflected on the fact that racism, as he had experienced it in church life, was a “monumental betrayal of the Christian ethic.” He returned to the U. S. resolved to adopt Gandhian ideas in his pastoral work. For example, he established an interracial congregation known as the “Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples.” In the 1950s, Thurman accepted a position as chaplain and professor of spiritual disciplines at Boston University where Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968) studied. A close friend of the family, Thurman urged King to adopt nonviolence through loving rather than demonizing opponents. In the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956, King carried a copy of Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited.

From the Howard Thurman and Sue Bailey Thurman Collections, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

In an essay entitled “Peace Tactics and a Racial Minority,” Thurman wrote:

At the very center of the Christian faith, even the enemy must be loved. The injunction is, “But I say unto you, love your enemies, that you may be children of your Father who sends His rain on the just and the unjust.” It is clear and needs no underscoring that what seems to be the natural thing is to hate one’s enemy. The insistence here is that the individual is enjoined to move from the natural impulse to the level of deliberate intent. One has to bring to the center of his focus a desire to love even one’s enemy.

A prolific author, Thurman placed Gandhian ideas at the heart of his ministry. Today, many regard him as the spiritual godfather of the civil rights movement.

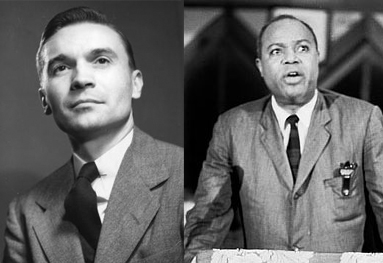

India provided the backdrop to an initiative in an impoverished area of New York City known as Harlem. James Herman Robinson (1907-1972), African-American pastor of a Presbyterian congregation, believed people could be organized to end racial segregation. He encouraged a local IFOR chapter to create an interracial ashram, a spiritual community in India. The Harlem Ashram existed from 1940 to 1946.

James Herman Robinson (1907-1972), African-American pastor of a Presbyterian congregation, encouraged a local IFOR chapter to create an interracial ashram, a spiritual community in India. The Harlem Ashram existed from 1940 to 1946.

The first (white) members circulated a broadsheet addressing the question, why had they chosen to reside in a part of New York City in which residents were largely African-American or Puerto Rican.

WE LIVE IN HARLEM BECAUSE:

We regard the problem of racial justice as America’s No. 1 problem in reconciliation, and most of our work concerns the Negro-white aspect of this problem.

Living here makes it easy for us to contact Negro leaders.

Harlem is the opinion-making center of Negro America, the Negro capital of the nation.

Living here helps us who are white to get something of the “feel” of being a Negro in America.

Almost at once, three African-Americans joined. All were Christian. A Hindu from India also joined the core group. The ashram included single men and women as well as families. Located at 2013 Fifth Avenue, near 125th Street, the ashram was near FOR’s office. Residents were FOR members.

The Harlem Ashram exemplified primitive Christian communalism as described in the Biblical book of Acts 2: 42-47 and Acts 4:32-35. Adopting voluntary poverty, each member gave according to her or his ability and received according to his or her need. Each contributed to the common purse that part of his or her income they were led to give and withdrew only what was needed. Living in solidarity with the wider Harlem community, members served by

- helping African-Americans migrating from the South to find housing;

- investigating the use of violence by the police in strikes;

- creating a credit union run by and for African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, and other minorities;

- organizing neighbors into a cooperative buying club;

- conducting play activities for children on the streets of African-American and Puerto-Rican neighborhoods.

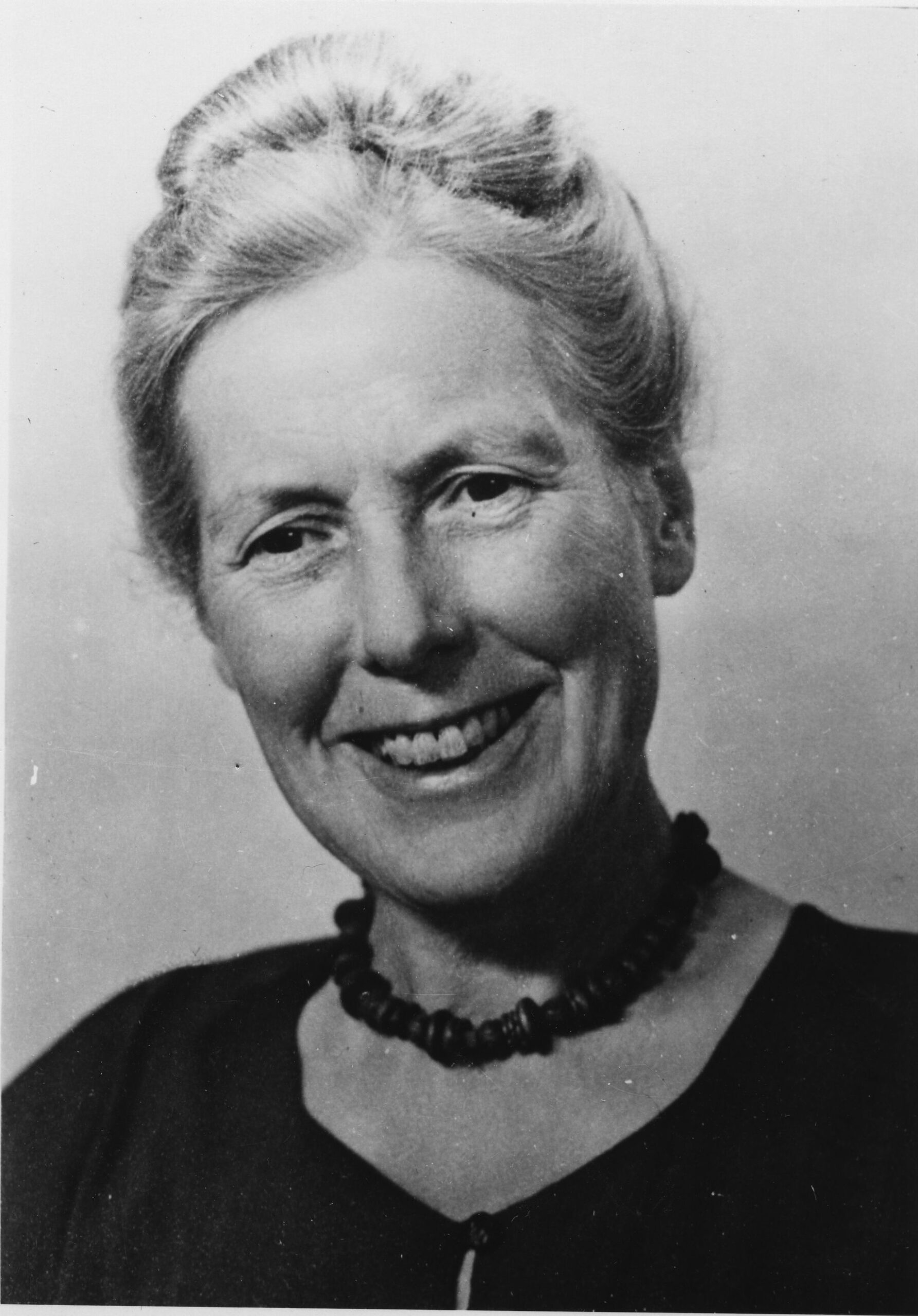

Among speakers who addressed the community, Muriel Lester (1883 –1968) was an English friend of Gandhi, traveling secretary for IFOR, and founder of a community in London called Kingsley Hall. Gandhi stayed there in 1930-1932 when he attended the Round Table Conference, a series of meetings in three sessions called by the British government to consider the future constitution of India.

In the early 1930s, Lester lectured in the U. S. where she shared her experience of Gandhi’s nonviolent undertakings. At the Harlem Ashram, Lester helped shape a course on “total pacifism.” Members studied books on Gandhi including Romain Rolland’s Mahatma Gandhi (1924), Charles Freer Andrews’ Mahatma Gandhi His Life and Works (1930), Richard Gregg’s The Power of Nonviolence (1935), salt march veteran Krishnalal Jethalal Shridharani’s War without Violence (1939), and Nonviolence in an Aggressive World by labor leader and onetime FOR executive director A. J. Muste (1940).

The Harlem Ashram provided a bridge by which nonviolent direct action techniques crossed from India to North America. Harlem Ashram members successfully campaigned to desegregate New York City’s YMCAs. In 1942, members undertook a two-week interracial pilgrimage. Fourteen persons walked two hundred and forty miles from New York to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D. C., to support anti-lynching and anti-poll tax bills before the U. S. Congress.

To develop satyagraha in the struggle against racism, FOR staff John M. Swomley Jr., a white, and James Farmer, an African- American, roomed together in Chicago where they helped form the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE). Members protested quotas before local boards of education and in Washington, D. C. for an anti-lynching bill before Congress.

FOR encouraged local chapters to deal with race prejudice in employment, housing, and public facilities such as prisons. On weekends, FOR staff conducted Race Relations Institutes in northern cities. Programs typically began on a Friday night. Various theologians would give a talk. Scientists gave presentations on the similarity of blood types of whites and blacks. Need for this initiative arose during World War II, when segregationists objected to blood transfusions from African-Americans for white casualties. Saturday activities generally involved direct action with the goal of integrating establishments such as a restaurant, theater, or bowling alley.

(https://pilgrimpathways.wordpress.com/)

In June 1943, two FOR staff members, Farmer and Swomley went to Detroit after a race riot where a local chapter sought to mediate. On another occasion, Rustin went to Boulder, Colorado, and worked with Marjie Carpenter, a student and member of the campus chapter of FOR, to organize a sit-in at an off-campus drugstore-sandwich shop. The demonstration led to making services available to everyone, African-Americans included. FOR also campaigned to prevent the Pentagon from making wartime conscription universal after the war.

FOR worked to desegregate public transportation. In 1945, staff members George Houser and Bayard Rustin proposed an action that proved the most daring one FOR had undertaken to date. Having resolved to challenge Jim Crow laws in interstate travel, they floated several ideas. The one that engendered the most support, and debate, was a two-week freedom ride called the Journey of Reconciliation.

Two key NAACP leaders, Walter White and future U. S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall resisted this kind of direct action as potentially counter-productive. Marshall warned that a “disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieve.” From April 9 to 23, 1947, the interracial team road a bus through fifteen cities in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Along the way, the freedom riders spoke at meetings organized by churches, colleges, and civil rights groups.

In several cities, local officials arrested participants, who welcomed an opportunity to present their arguments in a court of law. In one North Carolina case, judge Henry Whitfield ruled that the defendants had violated the state’s Jim Crow laws. He found the behavior of the European Americans–Joseph Felmet, Andrew Johnson, and Igal Roodenko– “especially objectionable.” In sentencing team members, Judge Whitfield admonished, “It’s about time you Jews from New York learned that you can’t come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave you black boys thirty days, and you whites ninety.”

Trained in Gandhian tactics, participants did not respond to violence with violence. They demonstrated the promise of nonviolent direct action, without which, they believed, the Jim Crow pattern in the South could not be broken. Many African-Americans discovered that they were not alone in their struggle for racial justice. Many were arrested and able to contribute to moderating the way prison guards treated people of colour. The first “freedom riders” successfully tested court decisions outlawing discrimination in interstate travel.

In 1948, an African-American FOR staff member Bayard Rustin spent a month in India where he had conversations with young intellectuals who urged him to help shape a mass movement in the U. S. modeled on Gandhian satyagraha. One of the organizers of the August 20, 1963 March on Washington, Rustin headed the U. S. chapter of War Resisters International and worked with other leading civil rights organizations including the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and CORE.

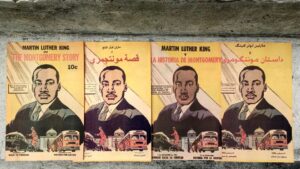

FOR deputed staff to work with Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Montgomery bus boycott and later to conduct workshops and other actions throughout the South. In 1955, FOR published a full-color comic book, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, which has had wide influence.

For example, future Georgia Congressman John Lewis read the comic book as a teenager. The comic book demonstrated in clear fashion to Lewis the power of the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence. Later, he attended weekly meetings with other students from Fisk University, Tennessee State University, Vanderbilt University, and American Baptist College to discuss nonviolent protest, The Montgomery Story served as one of their guides.

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story has been translated into several languages, including Spanish, Farsi, and Arabic. Most recently, during the so-called Arab Spring, thousands of copies in Arabic circulated among protesters in Tunisia and Egypt.

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story has been translated into several languages, including Spanish, Farsi, and Arabic. Most recently, during the so-called Arab Spring, thousands of copies in Arabic circulated among protesters in Tunisia and Egypt.

From February 2 to March 10, 1959, Martin Luther King, Jr. toured India accompanied by Coretta Scott King and Lawrence D. Reddick, African-American professor at Alabama State University in Montgomery. Returning, King commented on the relevance of India for those seeking racial and economic justice in the U. S.

I left India more convinced than ever before that nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom. It was a marvelous thing to see the amazing results of a nonviolent campaign. The aftermath of hatred and bitterness that usually follows a violent campaign was found nowhere in India. Today a mutual friendship based on complete equality exists between the Indian and British people within the commonwealth. The way of acquiescence [to violence] leads to moral and spiritual suicide. The way of violence leads to bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers. But, the way of nonviolence leads to redemption and the creation of the beloved community. (A Testament of Hope, p. 25)

Early in the civil right movement, campaigns exhibited deep commitment to nonviolence in all forms struggle to advance the equality of everyone, especially the most vulnerable such as children, adolescents, the elderly, or the disabled. In 1963, during the Birmingham campaign, Martin Luther King, Jr. set forth a radical action-plan for culture change. King required each participant in protests to abide by the following “Ten Commandments:

- Meditate daily on the teachings and life of Jesus

- Remember always that the nonviolent movement in Birmingham seeks justice and reconciliation—not victory.

- Walk and talk in the manner of love, for God is love.

- Pray daily to be used by God in order that all men might be free.

- Sacrifice personal wishes in order that all men might be free.

- Observe with both friend and foe the ordinary rules of courtesy.

- Seek to perform regular service for others and for the world.

- Refrain from the violence of fist, tongue, or heart.

- Strive to be in good spiritual and bodily health.

- Follow the directions of the movement and of the captain on a demonstration. (Why We Can’t Wait p. 61)

Dr. King drew the phrase “beloved community” from the ethical and pastoral discourse of his father and key African-American mentors such as Benjamin Mays and Howard Thurman, as well as social gospel pioneers Josiah Royce and Walter Rauschenbusch. For King, the beloved community entailed the realm of God coming to be. A foundational ideal of the U. S., African-Americans could actualize the dream by loving action. King observed,

… love might well be the salvation of our civilization. This is why I am so impressed with “freedom and Justice through Love” [motto of the Montgomery Improvement Association]. Not through violence; not through hate; no, not even through boycotts; but through love. It is true that as we struggle for freedom in America we will have to boycott at times. But we must remember, as we do so, that a boycott is not an end itself; it is merely a means to awaken a sense of shame within the oppressor and challenge his false sense of security. But the end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the beloved community. (Fellowship Magazine, 1957)

Fifty-two years after the death of King, the beloved community is not yet reality. Despite contrary evidence, I believe the dream still has power to motivate people to walk the road of peace and justice. As a Quaker, I define the dream as described in the mission of the American Friends Service Committee: “We seek a world free of war and the threat of war; we seek a society with equity and justice for all; we seek a community where every person’s potential may be fulfilled; we seek an earth restored.” While there has been significant progress in some areas, I do not believe there can be peace on earth until, as described in a United Nations document, all children daily eat their fill, go warmly clad against the winter wind, and learn their lessons with a tranquil mind. And thus released from hunger, fear, and need, regardless of their color, race, or creed, look upward smiling to the skies, their faith in life reflected in their eyes.

I close sharing my three basic ABCs.

Awareness: a personal experience of social ill, and that of others. I carry in my diary Gandhi’s Talisman, which invites me to reflect on how I might concretely address a human need, as follows:

Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you, apply the following test. Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man [woman] whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him [her]. Will he [she] gain anything by it? Will it restore him [her] to a control over his [her] own life and destiny? In other words, will it lead to swaraj [freedom] for the hungry and spiritually starving millions? Then you will find your doubts and yourself melt away. (Gandhi, The Last Phase, Vol. II (1958), p.65)

Begin with locally. Over the years, the Gandhi Peace Festival has undertaken grass roots mobilization, for example by promote a culture of peace and supporting specific projects such as the peace garden at Hamilton City Hall, where there is a statue of Gandhi, or women in India.

Confidence: we can make a difference; never underestimate the “power of one.” The anthropologist Margaret Mead is often quoted as follows: “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” African-Americans express this as follows, “I am a somebody.” In words of Howard Thurman,

There is in every person an inward sea, and in that sea there is an island and on that island there is an altar and standing guard before that altar is the ”angel with the flaming sword.” Nothing can get by that angel to be placed upon that altar unless it has the mark of your inner authority. Nothing passes ”the angel with the flaming sword” to be placed upon your altar unless it be a part of ”the fluid area of your consent.” This is your crucial link with the Eternal. [Meditations of the Heart, cited https://gatheringinlight.com/2019/02/14/an-inward-sea-by-howard-thurman/]

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Paul R. Dekar is author of several books, including Creating the Beloved Community: A Journey with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (2005); Dangerous People: The Fellowship of Reconciliation Building a Nonviolent World of Justice, Freedom, and Peace (2015); and the forthcoming Thomas Merton: God’s Messenger towards a New World (2020). An emeritus professor of evangelism and mission at Memphis Theological Seminary, he also served as chairperson of FOR-USA’s National Council from 2008-10. Paul now lives in Dundas, Ontario, Canada. [/author_info] [/author]