African-American leaders vowed, days in advance of any court announcement, there would be mass protests in the St. Louis area if former cop Jason Stockley was found not guilty of murdering Anthony Lamar Smith. Thus, moments after Judge Timothy Wilson announced on Sept. 15 he was acquitting Stockley — and repeating the vile national pattern of police not being held to account for killing African Americans — activists en masse indeed did take to the streets.

Many thousands have joined in actions since then on a near daily basis across the metro area, with more than 300 arrested in nonviolent protests organized by a leaderful group of African Americans. Such disciplined resistance offers perhaps the best hope to compel progressive, constructive change and provides a vent for a growingly impatient public — blacks and white allies alike, angered with continuing centuries-long systemic racism and the institutionalized devaluation of black life.

The ugly consequences of justice, persistently denied, have become evident at times in St. Louis the past few weeks, just as they were clear to Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. He steadfastly advocated for nonviolent tactics in advancing civil rights, yet recognized that “Riot is the language of the unheard.”

Many of the black women and men leading this robust nonviolent resistance came together during months of protests following the Aug. 2014 police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, which helped galvanize the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement. Activists over the past month have disrupted business as usual in various venues across St. Louis, for instance by shutting down major thoroughfares in front of city hall, various police departments, and a section of Highway 64/40 downtown, plus interruptive actions at sporting events and shopping centers.

Since Stockley’s acquittal, I’ve spent eight days in St. Louis, honored to join protests and meet-ups as a representative of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (thanks to the encouragement and support of FOR leaders Dr. David Ragland and Ethan Vesely-Flad).

Familiar, straightforward chants like, “No Justice, No Profits,” “If We Don’t Get It, Shut it Down,” and “The People United Will Never Be Divided” — often accompanied by drumming — animate the passionate actions. That first chant particularly resonated for me, as I joined a few hundred other protestors when we boisterously wound through the upscale St. Louis Galleria shopping center on Sept. 23rd. Many workers shut their shop doors while consumers were compelled to divert their attention to the protesting presence.

Various videos captured by individuals on their cell phones, then posted on YouTube, show what religious and civic leaders later accurately termed “a police riot” during a news conference the following Monday. As the protest was concluding, organizers noted, white cops from the St. Louis County and Richmond Heights police departments mobilized violently.

It seemed to me they singled out some African-American women and a 13-year old male youth. Many of us nearby reacted with concern, urging their release and those of others, whites and blacks, who were subsequently detained. There was, among the now so-called “Galleria 22” arrestees (similar to other actions across the area), a cascade of compassion shown by folks — many, formerly strangers to one another, united now in our offense to police brutality and arbitrary actions.

Twenty-two of us were arrested, including three bystanders swept up by zealous cops. Befitting the hypocritical doublespeak of these times, prosecutors charged seven of us with rioting, interference with official acts and/or assaulting a police officer. None of us had planned to risk arrest, but dissent, particularly in such a rather high-end cathedrals of consumerism, was apparently intolerable. If only such intolerance was shown by officials for the killing of African Americans.

Twenty-two of us were arrested, including three bystanders swept up by zealous cops. Befitting the hypocritical doublespeak of these times, prosecutors charged seven of us with rioting, interference with official acts and/or assaulting a police officer. None of us had planned to risk arrest, but dissent, particularly in such a rather high-end cathedrals of consumerism, was apparently intolerable. If only such intolerance was shown by officials for the killing of African Americans.

Cops at the Galleria mall threw several people to the floor, including me (I sustained and was treated for a concussion due to the violence). As one cop kneeled heavily upon my neck, I recall experiencing a pang of empathetic clarity, emerging from my skin-deep unearned white privilege.

Painful, vulnerable positions like this are all too commonly experienced by so many African American brothers and sisters (racist micro-aggressions experienced by, quite likely, all black residents of this country) during the course of their lives. It’s also incumbent I realize that my whiteness typically continues to buffer me against such mistreatment — indeed, inappropriate for anyone to experience, and particularly not because of one’s skin color.

Rodney Brown, an African-American activist among our group of seven who are facing a possible trial for the Galleria protest, noted at the jail that it was heartening to have many Euro-Americans, not just blacks, participating and being arrested. (Indeed it seemed that white people comprised more than half of the activities I attended.) Essential societal change, such as ending police brutality and holding cops to account for wrong-doing can take place — but only with the continued and expanded activism by more people, especially white folks, taking greater risks with nonviolent actions and following the lead of affected blacks on the ground.

If officials remain intransigent and refuse to heed the reasonable demands of this nonviolent resistance, the public has seen glimpses of an even more ugly potential future these past few weeks. On Sept. 16, for instance, perhaps a thousand people — angry over the acquittal but disciplined — marched for a few hours throughout University City during the evening, shutting down several streets. At about 9:00 p.m., organizers announced the planned protest was over.

Most people left, but as had been the case the previous night, perhaps a hundred lingered longer. Incensed with the lack of accountability for Anthony Smith’s murder, this second wave of protestors on Delmar Street also chanted in anger, but included a few individuals who advanced up to cops behind plastic shields, taunting and cursing at them. During a tense half-hour, several of us tried, ultimately without success, to discourage a few young people from, first, throwing water bottles, then even a few bricks at the circle of police.

Officials reported 11 officers were injured. A group of cops in full riot gear then deployed down Delmar Street, as several young men began running down the sidewalks throwing chairs, trashcans, and other objects, in the process breaking storefront windows of many businesses. Cops fanned out and arrested perhaps a dozen people suspected of causing property destruction.

The next morning, I joined dozens of people, black and white, who showed up to help business owners clean up the damage. While deplorable, such destruction can be inevitable when officials persistently fail to correct inequities and through amoral inaction (plus contemptible brutality), suggest that to them, black lives, like those of Anthony Smith, Michael Brown, et. al. — simply do not matter.

The next morning, I joined dozens of people, black and white, who showed up to help business owners clean up the damage. While deplorable, such destruction can be inevitable when officials persistently fail to correct inequities and through amoral inaction (plus contemptible brutality), suggest that to them, black lives, like those of Anthony Smith, Michael Brown, et. al. — simply do not matter.

My hope in the ultimate countervailing strength of exercised people power was rekindled yet again as a few hundred people of diverse ages and race gathered last week, on Oct. 16, for a meet-up at the Wayman African Methodist Episcopal Church. Seven leaders, black women and men, enthusiastically convened us as folks broke up into small groups and then reassembled, sharing visions of future actions and campaigns for greater social justice. Stay tuned!

All are welcomed and encouraged to support the resistance by donating to the St. Louis Legal Fund, which has helped free dozens of jailed protestors (including myself) by posting bond and assisting in providing legal representation. Learn more about the struggle and future plans via the Expect Us St. Louis Facebook page.

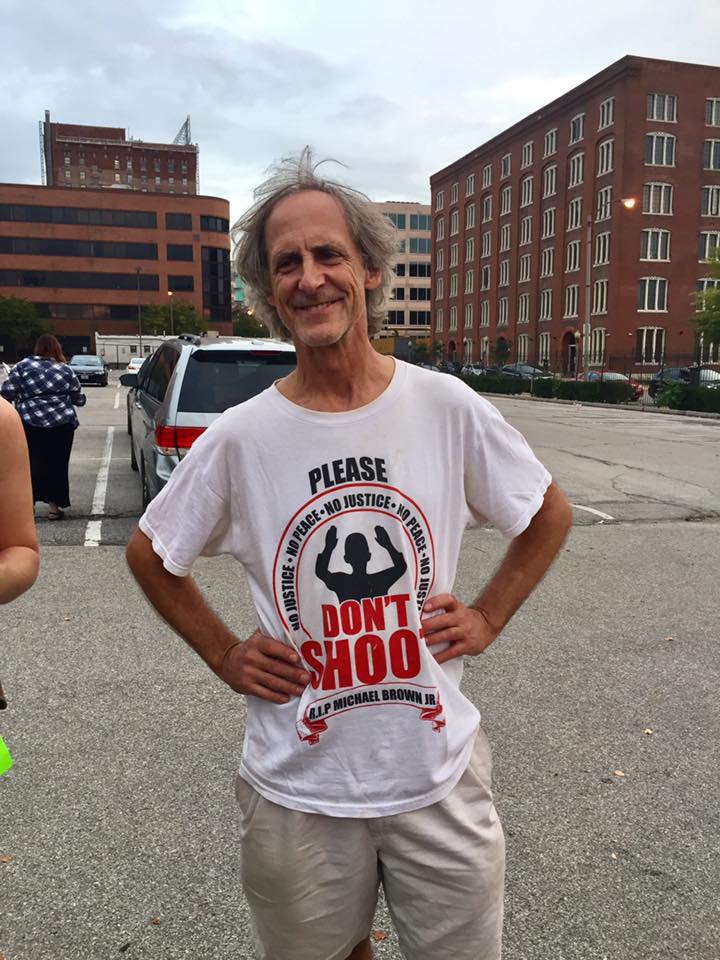

[Photos: (1) Drummers marching on Sept. 15, by Sharon Morrow; (2) St. Louis Police marching in riot gear on Sept. 15, by Paul Sableman, Flickr/Creative Commons license; (3) Jeff Stack among fellow protesters in St. Louis, by Sharon Morrow.]