By 1953, Bayard Rustin was by all accounts a successful player in the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In the 12 years he had worked for the organization, he had gone to prison as a conscientious objector, fought segregation in the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, and protested whenever he was denied service at restaurants as a black man. He was a popular speaker with college and high school students and, according to a contemporary issue of Fellowship magazine, had far more requests for speaking engagements than he could fit into his schedule.

By 1953, Bayard Rustin was by all accounts a successful player in the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In the 12 years he had worked for the organization, he had gone to prison as a conscientious objector, fought segregation in the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, and protested whenever he was denied service at restaurants as a black man. He was a popular speaker with college and high school students and, according to a contemporary issue of Fellowship magazine, had far more requests for speaking engagements than he could fit into his schedule.

But there was one aspect about Rustin that drew the ire of members and the staff of the FOR: He was gay, and he was relatively open about his sexuality.

“[Rustin] was offending these people” in the FOR, his psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Ascher said, “because he was so aggressively…even angrily in your face, ‘I’m a homosexual.’”

In early 1953, conflict within the FOR surrounding Rustin’s sexuality came to a head. It was at that time that Rustin was arrested on a so-called “morals charge” for having sex with two men in a parked car in Pasadena, California during a speaking tour funded by the American Friends Service Committee. The LA Times quickly reported on the arrest, the AFSC cancelled Rustin’s remaining speaking engagements, and the FOR office received calls demanding that Rustin be fired from the organization.

In the end, the organization agreed. By March, Rustin had resigned from the FOR.

The way that A.J. Muste, the executive director of the FOR at the time, and the rest of the FOR responded to Rustin’s Pasadena arrest, and his sexual orientation in general, is a dark spot in the organization’s history. The FOR failed to respond to Rustin’s sexuality with the same compassion that they offered toward victims of other forms of oppression.

Throughout his tenure at the FOR, Rustin’s homosexuality was known to staff members. Over the years, he had had numerous “incidents” or “episodes,” as FOR staff member John Swomley described them. According to Swomley, Rustin solicited the 18-year-old son of an FOR staff member. He was arrested once in New York City for a morals charge similar to the one in Pasadena in 1953, and, according to Swomley, there were other “incidents when Rustin was a guest in the homes of FOR members.”

Throughout his tenure at the FOR, Rustin’s homosexuality was known to staff members. Over the years, he had had numerous “incidents” or “episodes,” as FOR staff member John Swomley described them. According to Swomley, Rustin solicited the 18-year-old son of an FOR staff member. He was arrested once in New York City for a morals charge similar to the one in Pasadena in 1953, and, according to Swomley, there were other “incidents when Rustin was a guest in the homes of FOR members.”

It was partly, in fact, how open and promiscuous Rustin was that disturbed FOR members. The organization’s members spoke of Rustin’s homosexuality in hushed terms, referring to it as “Bayard’s problem,” according to biographer Jerald Podair; Rustin was not nearly as quiet about it. Rustin’s solicitation of the FOR staff member’s teenage son deeply angered the staff member.

But while it was Rustin’s promiscuity that particularly disturbed FOR members, the fact that he was gay provoked at least some of their concern. The FOR responded to Rustin’s behavior with an “insistence on rigid abstinence,” according to David Dellinger, a member of the Executive Committee of the War Resisters’ League. David McReynolds, who worked for the WRL in the 1960s, wrote that he was considered for the staff of the FOR by Glenn Smiley soon after Rustin’s departure, on the condition that he would “overcome my own homosexuality” with the help of therapy.

After the morals charge in New York City, Muste paid briefly for Rustin to get psychiatric help. “Muste, [Rustin’s] boss, felt that [homosexuality] was an illness and it needed to be treated psychiatrically,” Rustin’s partner, Walter Naegle, said in an interview with OUT Magazine this year. Muste himself insisted that “I keep my mind open” about “a-typical relationships,” but he nonetheless urged Rustin to discontinue “a certain type of relationship.”

Meanwhile, other staff members were a lot more narrow-minded in their treatment of Rustin. Prior to Rustin’s Pasadena arrest, the husband of a staff member had pressured Muste and the FOR to fire Rustin—a request Swomley wrote later influenced Muste’s decision in 1953 to pressure Rustin to resign. “I found some of the worst attitudes to gays” within the FOR, Rustin said in a 1987 interview with Open Hands. “…Many of the people in the Fellowship of Reconciliation were absolutely intolerant in their attitudes.”

When Rustin was arrested in 1953, no one seemed willing to have him stay with the FOR. In their minds, Rustin’s behavior was deplorable—first of all, because the incident was with other men; second, because it showed Rustin was continuing to act promiscuously; and third, because it generated publicity, which opponents to the peace movement could use to attack the cause. Typical were lines like this one from FOR member Allan Knight Chalmers to Muste: “[Rustin] has felt he could do as he wanted and could get away with it in not hurting the cause.”

Muste lamented that Rustin “engaged in practices…which a person with a tenth of your brains must have known would defeat your objectives” and decided that Rustin should resign from the organization. Rustin agreed and drew up a resignation for the FOR. In the following years, Muste and Rustin continued to speak with one another. Other members kept their distance.

Until his death, Rustin remembered the FOR’s treatment of his sexuality with a bitterness he did not give to any other organization. “When I lost my job [with the FOR], some of these nonviolent Christians despite their love and affection for humanity were not really able to express very much affection to me,” he said in his 1987 interview with Open Hands.

Over the years, the FOR has opened up considerably in its treatment of LGBT people. Starting in the 1980s, the FOR began to shift in its position on LGBT rights, and some members began writing to ask the organization to invite Rustin over for a formal reconciliation. Following his death, another member suggested the FOR formally apologize to Rustin’s partner, Walter Naegle. The meeting with Rustin never happened.

In the past 20 years, the FOR has made LGBT rights part of its agenda. In 2001, the FOR launched the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender & Queer Task Force, which has supported LGBTQ organizations in their fight for equal rights. In 2015, the FOR consulted Naegle in its creation of the Bayard Rustin Fellowship and apologized to Rustin in its autumn issue of Fellowship magazine.

Today, FOR’s executive director, Rev. Kristin Stoneking, is openly gay and works through the FOR to advocate for LGBTQ rights. She successfully helped the United Methodist Church, which she is a part of, to elect its first openly gay bishop this July.

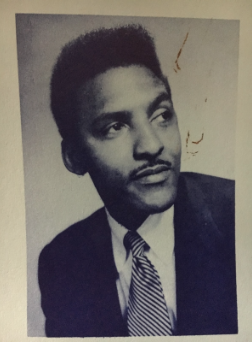

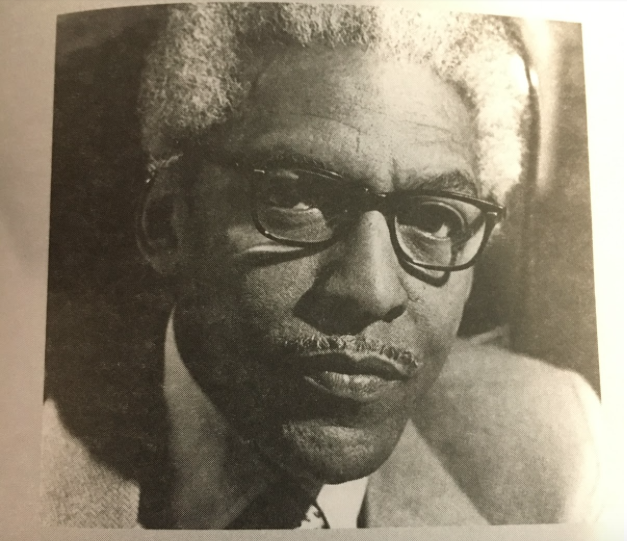

[images: 1) Bayard Rustin in 1952, from FOR Archives; 2) Bayard Rustin later, FOR Archives; 3) Rev. Osagyefo Sekou, the first Bayard Rustin Fellow, in St Louis, Missouri]