by Jim Forest

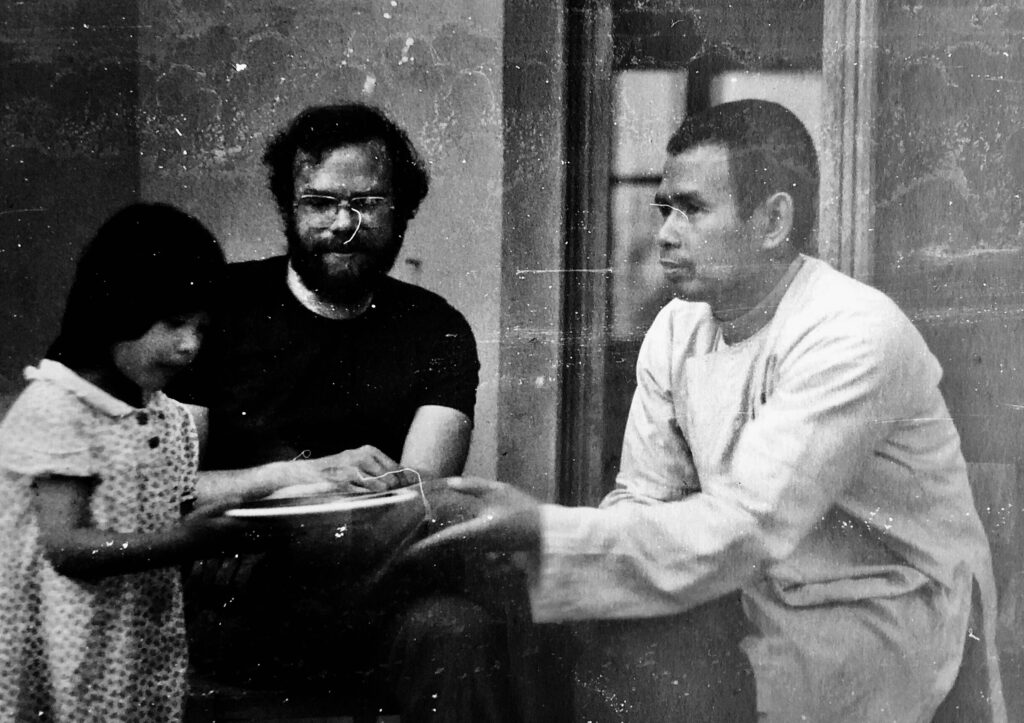

In 1968, I was traveling with Thich Nhat Hanh on a Fellowship tour during which there were meetings with church and student groups, senators, journalists, professors, business people, and (blessed relief) a few poets. Almost everywhere he went, this brown-robed Buddhist monk from Vietnam (looking many years younger than the man in his 40s he was) quickly disarmed those he met.

His gentleness, intelligence, and sanity made it impossible for most who encountered him to hang on to their stereotypes of what the Vietnamese were like. The vast treasury of the Vietnamese and Buddhist past spilled over through his stories and explanations. His interest in Christianity, even his enthusiasm for it, often inspired Christians to shed their condescension toward Nhat Hanh’s tradition. He was able to help thousands of Americans glimpse the war through the eyes of peasants laboring in rice paddies and raising their children and grandchildren in villages surrounded by ancient groves of bamboo. He awoke the child within the adult as he described the craft of the village kite-maker and the sound of the wind instruments these fragile vessels would carry toward the clouds.

“He was able to help thousands of Americans glimpse the war through the eyes of peasants laboring in rice paddies and raising their children and grandchildren in villages surrounded by ancient groves of bamboo.”

After an hour with him, one was haunted with the beauties of Vietnam, and filled with anguish at America’s military intervention in the political and cultural tribulations of the Vietnamese people. One was stripped of all the ideological loyalties that justified one party or another in their battles, and felt the horror of the skies raked with bombers, houses and humans burned to ash, children left to face life without the presence and love of their parents and grandparents.

But there was one evening when Nhat Hanh awoke not understanding but rather the measureless rage of one American. He had been talking in the auditorium of a wealthy Christian church in a St Louis suburb. As always, he emphasized the need for Americans to stop their bombing and killing in his country. There had been questions and answers when a large man stood up and spoke with searing scorn of the “supposed compassion” of “this Mr. Hanh.”

“If you care so much about your people, Mr. Hanh, why are you here? If you care so much for the people who are wounded, why don’t you spend your time with them?” At this point my recollection of his words is replaced by the memory of the intense anger which overwhelmed me.

When he finished, I looked toward Nhat Hanh in bewilderment. What could he – or anyone – say? The spirit of the war itself had suddenly filled the room and it seemed hard to breathe.

There was a silence.

Then Nhat Hanh began to speak – quietly, with deep calm, indeed with a sense of personal caring for the man who had just damned him. The words seemed like rain falling on fire.

“If you want the tree to grow,” he said, “it won’t help to water the leaves. You have to water the roots. Many of the roots of the war are here, in your country. To help the people who are to be bombed, to try to protect them from their suffering, I have to come here.”

The atmosphere in the room was transformed. In the man’s fury we had experienced our own furies: we had seen the world as through a bomb-bay. In Nhat Hanh’s response we had experienced an alternate possibility: the possibility (here brought to Christians by a Buddhist and to Americans by an “enemy”) of overcoming hatred with love, of breaking the seemingly endless chain reaction of violence throughout human history.

But after his response, Nhat Hanh whispered something to the chairman and walked quickly from the room. Sensing something was wrong, I followed him out. It was a cool, clear night. Nhat Hanh stood on the sidewalk struggling for air – like someone who had been deeply underwater and who had barely managed to swim to the surface before gasping for breath. It was several minutes before I dared ask him how he was or what had happened.

Nhat Hanh explained that the man’s comments had been terribly upsetting. He had wanted to respond to him with anger. So he had made himself breathe deeply and very slowly in order to find a way to respond with calm and understanding. But the breathing had been too slow and too deep.

“Why not be angry with him?” I asked. “Even pacifists have a right to be angry.”

“If it were just myself, yes. But I am here to speak for Vietnamese peasants. I have to show them what we can be at our best.”

The moment was an important one in my life, one pondered again and again since then.

(excerpted from “Like Rain Falling on Fire,” originally published in Fellowship, September 1975)

Quote:

“History demonstrates that nonviolent action requires creativity, thorough understanding of the mentality of the people, and above all, a resisting spiritual force. Organizational techniques are not sufficient for success.”

—from Nhat Hanh, “Love in Action: the Nonviolent Struggle for Peace in Vietnam,” (Fellowship, 1970)

About the author: Jim Forest, editor emeritus of Fellowship and former secretary general of IFOR, is an Orthodox Christian lay theologian, educator, and peace activist. His many books include Ladder of the Beatitudes; Loving Our Enemies: Reflections on the Hardest Commandment; and biographies of Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, and Daniel Berrigan.