By Laura Hassler

the pine gate closed

a scintillating arrow

leaves the

trembling string

air rips

the sun explodes

orange blossoms fall, fall cover the yard

There is the shadow

of infinity

nhat hanh

Written for Laura Hassler upon her return from Vietnam

Judy Forilla was my code name, for telegram messages back to Thich Nhat Hanh and Cao Ngoc Phuong (later Sr. Chan Khong), both living in exile in Paris. Thây had thought it up himself: my sister’s name, Judy, and a surname, with a wink: FOR-guerilla.

They needed a messenger to travel to Vietnam on their behalf, and my father, Alfred Hassler, then executive secretary of the FOR and a key ally in the West, could no longer get an entry visa. I was a budding peace activist, working for a humanitarian medical organization for war-injured Vietnamese children, so I had a sort of cover. Alfred asked me to go.

Thich Nhat Hanh had been a welcome guest in our family’s home many times; he and Alfred had become not only strategic allies but also close friends. Their current plan, a collaboration between the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation and the International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam, was the Stop the Killing Campaign. The campaign’s appeal for a cease-fire had been signed by prominent theologians, educators, and parliamentarians around the world and would be published and promoted internationally.

My “mission” would be to persuade student activists, Buddhist movement leaders and as many members of the south Vietnamese National Assembly as possible, to sign the call for a cease-fire — a risky act in a place known for political persecution, tiger cages, and torture. But the war-weariness by now was so great that Thây and Phuong counted on support from their colleagues and student activists and calculated that some parliamentarians might dare to join the campaign, making it stronger.

In the pre-Internet age, with letters intercepted and phones tapped, only a personal emissary could be trusted with personal messages. And so, with hand-written messages from Thich Nhat Hanh hidden in my tourist maps and toilet kit, I arrived alone at the Saigon airport.

It was early December, 1971. I was 23 years old.

A few months later, I would move to Paris, at Thây’s invitation, to join the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation’s small team, helping to edit and write letters and newsletters, hosting guests, and occasionally doing short speaking tours on their behalf.

My “spy mission” had been successful, but the Stop the Killing Campaign had not. Even the Western peace movement would not throw its full support behind the campaign, being by then split between those who insisted on a total U.S. withdrawal as condition to a cease-fire, and those who, following the nonviolent Buddhist movement, urged an immediate, unconditional end to the killing. The peace movement, fractured and turned against itself, lost whatever power and moral leadership it had once commanded. On December 26, Nixon ordered the resumption of the bombing of North Vietnam, and the war and all its misery would groan on for another three years.

“Americans cannot be peacemakers until they learn how to breathe.”

With no more political solution in sight, the Buddhist movement in Vietnam now focused on saving what lives it could, and the work of our office was devoted to supporting those efforts: raising money for the care of orphans and widows, collecting donated medicines for Buddhist hospitals and clinics, publicizing news of clergy arrested for their activism.

The Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation had been authorized by the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam to represent it at the Paris Peace Talks. But despite speaking on behalf of one of the largest mass nonviolent movements of the century, they were never invited to attend those talks.

The Delegation did its best to represent its constituency by responding to developments at the talks and in Vietnam, and by advocating, in every way it could, an immediate end to the war. It also engaged with, and tried to persuade, U.S. and European peace movements to support its work. There were many wonderful supporters, who often became close friends. There were also attacks and false charges, from left and right, that made me so angry. But I was not allowed to respond in their defense: “It is not our way.”

I lived with that little Buddhist community for about a year. When I think back on that time, the first word that comes is grief. And the second is joy. It was a period of a kind of hopeless uncertainty, when it seemed the war would never end, and the stream of bad news would never stop. But neither did they stop. It was not that Thây, Phuong and their little team were tireless – I could see the tiredness in their eyes and hear it in their voices. But they were present, they were in touch with the suffering, and therefore incapable of not responding.

The joy was also in that presence: a quiet walk in the woods, growing herbs in pots or Vietnamese vegetables in a small garden, drinking tea together, listening to Phuong’s lilting voice singing traditional Vietnamese songs. They loved my Woody Guthrie songs, especially “Union Maid” and “Mail Myself to You”: “Laura, sing ‘stick some stamps!” – with the laughter already in the request.

A memory: one afternoon, we welcomed an American peace activist, who had asked for an interview with Thich Nhat Hanh. She came with her then-state-of-the art cassette recorder and her yes-or-no type of questions, trying to pin a Zen master down to Western dichotomies.

The cassette recorder ran, jammed, stopped, and answers were interrupted, cassette rewound, questions repeated, answers tried again. As the tea cups grew cold, the interviewer became more and more agitated, frustrated both by the subtle mind of her subject and the challenges of modern technology.

When she finally left, the room was quiet. Thây poured another cup of tea and sighed.

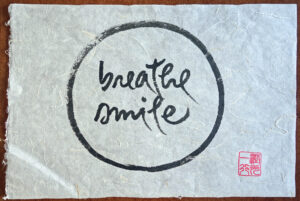

“Americans cannot be peacemakers,” he said, “until they learn how to breathe.”

His unbelievable success and impact in the post-Vietnam war period are, I believe, due to his decision to do exactly that: teach people how to breathe so that they may become peacemakers. I so long for the next global peace movement, one that knows how to breathe and be present, that acts tirelessly on behalf of all life on our interconnected planet, and also knows the joy of sharing a song and a cup of tea.

Here is my own very young poem, after that trip to Vietnam so many years ago:

Nhat Hanh

Your life is a poem

Images in the minds of people

Visions of a hoped-for world

We who lack patience

See the earth enduring the longest winter

We who lack humility

See a mother begging bread for her babies

We who need a reason to hope

Sometimes we see nothing

But a small star sits on the horizon

Never setting

About the author: Laura Hassler is founder and director of Musicians Without Borders. She is the daughter of Al Hassler, former executive secretary of FOR.